Gam’s outfit in the coffin was all wrong. I know Ma wanted her to look good, but Gam wouldn’t have picked that blouse. It was a deep navy, polyester posing as silk, with ruffles down the front. Continue reading

Karyn

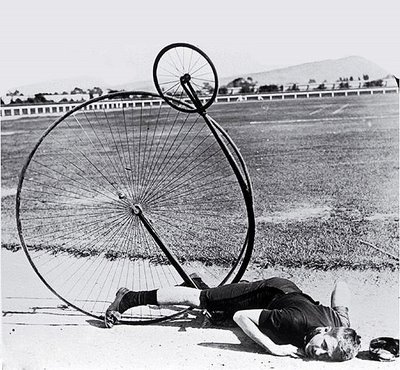

This spill…was special.

I knew I was in trouble after I’d spent ten minutes crawling around on concrete in the 25 degree weather, in the icy breeze blowing off the lake, looking for a tooth that may, at one time, have been in my mouth, without success. The part of brain not in crisis mode and still well-acquainted with my Girl Scout training said, “Say, I understand you’re concerned about spitting out mouthfuls of blood but do you think you should still be on the ground in icy weather when you might be going into shock? I mean, don’t you think your dentist could just make you a new tooth, if need be?” This is the part of my brain that likes to sprawl on a ledge overseeing the panic neurons as it relaxes with a glass of Riesling.

I want to start by saying the case of Baby Joseph is heartbreaking.

This little boy, only fifteen months old, is suffering from a terminal illness. He’s going to die. His Canadian doctors said if the boy was taken off a ventilator at at his most recent hospitalization, he would die. Those doctors refused to perform a tracheotomy on him. So the parents started asking doctors in the US for help. The Children’s Hospital in Detroit was among those that said no. SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in Saint Louis said yes.

Continue reading

Dorky songs on your workout playlist! C’mon, we all have them.

What’s on your workout list?

If you’ve read my article about me boxing, you know I get INTO that shit. I like songs that pump up and kick ass.

Tops on my list:

- The Theme to Rocky. Of course. Because that’s the Nor’Easter running past you, through Queens, on her way to Philadelphia, where I’m going to run up those steps someday.

- “Eye of the Tiger” — the Survivor Version and the Gloria Gaynor version

- “I Will Survive” — speaking of Ms. Gaynor

- “We’re Not Gonna Take It” — Twisted Sister. Because I’m not going take it. I’m going to punch you, mofo.

- “Cum On Feel the Noize” — Quiet Riot. Yeah, I said Quiet Riot. Not Slade.

- “Theme to St. Elmo’s Fire” — because I am where the Eagles are flying, higher and higher

- “Straight Outta Compton’ — N.W.A. I could not be less outta Compton. I am a white woman from the suburbs of Boston. But I wrap up my hands and throw punches to this sweet ditty, I am gangsta.

- “Back in the Saddle” — Aerosmith. Because I am Boston girl, and I would love to play horsie with Steven Tyler.

I’m sorry, was that last one out loud?

Why do you hate me?

I mean, you’re lucky I saw you. Happily cruising in the bike lane in along 34th Avenue in Queens, watching warily, as I usually do, for cars that don’t bother to signal before pulling out from parking, or people who open doors without looking, or drivers who think the bike lane is a passing or turning lane—you stepped out from between two parked SUVs, in the middle of block, not looking at oncoming traffic, holding the hand of a little girl who was clutching a wrapped birthday present.

Thank God I’d just gotten my bike tuned up for spring, complete with new brake pads. I can stop on a dime. You stepped forward. You stepped back. That made it difficult to ride around you.

So I said, “Excuse me.”

This uncorked a fury inside you. You screamed at me, throwing F-bombs like Mellissa Leo at the Oscars, yelling about how you had more right to be here than me, how I don’t own the street, how I need to leave him alone, how I should go and lose some weight (you lost five points for creativity there, buddy).

New Yorkers are angry at people who ride bikes. Let’s explore why.

First off, bike lanes take away room for cars. There’s no getting around that. Bike lanes take away driving lanes in some cases, and parking spaces in others. It’s interesting that everyone agrees we need to encourage less driving in the city, but no one wants to give up their cars.

That’s the least of the problem. Biking’s problem is that the major cycling advocacy groups have no clue how to win over the public.

Some suggestions:

Cycling advocates need to back cops when they hand out tickets for cyclists committing traffic violations. You want to be treated with respect, helmet-people? Well, start earning it. You’ve got to stop at red lights. You’ve got to yield to pedestrians. You’ve got to stop wearing headphones while biking. Make sure your bike is equipped with the reflectors and bells and lights required by law. Don’t argue with the police officer who stops you for not stopping at a light. She’s only doing her job. When a police officer is directing traffic, his directives also apply to you—not just the cars behind you. Don’t ride on the sidewalk. When the street is too dangerous, dismount and walk. When Central Park is crowded, slow down. This ain’t the Tour de France. In other words, act like adults.

Next: Use that record of law-abiding good behavior to demand from your city representatives that police go after drivers who make conditions unsafe for everyone—other cars, pedestrians, and cyclists. When was the last time you saw someone make a full stop at a stop sign? Stop for a pedestrian in a crosswalk? Use signals on a regular basis? That this driving behavior is allowed to continue unfettered in this city is outrageous.

Can we just get rid of Time’s Up and its ilk? There is a difference between persistence and aggression. Groups like Time’s Up push aggression, hoping to shove bike lanes and bike infrastructure into place. No one likes change to be shoved at them. Present. Sympathize with the opposition. And be willing to compromise. More can be done with talking than with fighting.

Don’t respond to fire with a container of gasoline. When the conservative population in Willamsburg got upset about a bike lane there—largely, it was alleged, because women rode bikes in “immodest clothing” (I wonder how my bike tights would be taken there) the hipsters organized a protest which involved them riding their bikes naked. Turns out it was too cold to ride naked, so the group largely backed out, but that’s not helping. Cyclists came off as a group of entitled brats with a complete lack of respect for everyone around them. That’s not to say the conservatives were right. But it would have been very easy ride onto high road, rather than the low.

Lastly, play nice. Let a car go past you. They’re faster. And heavier. Let an old lady cross the street. Remember this isn’t a race. Realize you’re not the only person on the road. And don’t yell back at peckerheads.

Sometimes the subways melt together, fuse, split apart and rise again, utterly different. Sometimes it happens slowly, and sometimes it happens in the course of a single stop.

Sometimes, Manhattan’s fabled street grid shifts, or tilts, making north become east and east become south.

My brain doesn’t accept direction, or distance, or shapes, or numbers the way most people’s brains do. In most people, there is an instinctual sense of direction. In me, there is not. I’m learning disabled in spatial relationships, affecting how I deal with things in space and time, and how I process non-verbal information. I can’t tell my left from my right unless I’m wearing my watch, which I understand, because I’ve memorized this fact, is on my left wrist. Even then, I have to think about it for a second. This was the main reason I didn’t learn to drive until I was twenty-two, after failing one drivers’ test and then getting a good word from a State Trooper friend whose barracks regularly got cookies from me in my reporting days.

The constant flogging from teachers and parents when it came to my math problems: You’re not trying hard enough. You’ve got to pay attention. I didn’t understand how crying at my desk wasn’t trying hard enough. It started with the shoes — all my classmates in first grade could tie their laces. I was still figuring it out in third grade. Thank God the mid-eighties Velcro trend kicked in. That only helped if I could put the damn things on the proper foot. Even now, at thirty-seven, I mark all my boots with a Sharpie so the left one doesn’t go on the right.

The problems were not officially noticed until I was in my second round of pre-algebra in high school. The teacher was your classic arithmetic teacher with chalk dust covering his pants and crooked glasses on his end of his nose kind of person and found it unusual that the editor of the high school paper was in the same math classes as the kids who showed up twice a week. I was sent to the school shrink (hysterically named Dr. Brain) who sat me down and asked me to put a simple puzzle of an elephant together.

I couldn’t do it.

“I don’t know how you’ve gotten this far,” he said. I was about to enter my senior year of high school, too late for remedial training, unless the school system kept me back a year. I had already been accepted to Emerson College, which openly said it did not care about a journalism major’s math scores.

I’ve learned to get around. I plot a trip to the mall like a Marine launching an offensive in Afghanistan. I play word association games to remember my parking spaces. (Section F is for a FANTASTIC space!) I make friends with mannequins upon mall entry, remembering their outfits as my entry/exit points. I go out of my way to use, say, the escalator by the tacky indoor waterfall to help remember my route through the retail wasteland, since the mall maps mean nothing to me. I feel my way though like a firefighter in a building filled with thick smoke, searching by hand, by touch, for The Body Shop.

I have gotten lost in giant Targets and Walmarts, desperately pawing through knockoff handbags for whomever may be my shopping companion. My mother still thinks it’s a riot to move her carriage over a few aisles and see if I’ll figure it out. We’ll see who’s laughing when Nursing Home Time comes.

At home, I foolishly refuse to accept my limitations, attempting to assemble cheap furniture and managing to put it together upside down and backwards. My husband, ever kind and patient, takes it apart and assembles it properly.

You’ll probably see me, the only person in Manhattan taking a compass out of her bag to figure out where she is in Midtown. Or maybe confused in a hospital, lost going to the doctor I’ve seen dozens of times. Or maybe in my own neighborhood, somewhat discombobulated having gotten off at the wrong subway exit and launched myself south instead of north. You’ll see me in a restaurant, using a tip calculator on my Blackberry to figure out a twenty percent tip on a ten dollar bill. I might show up for work when I’m not scheduled, because I have trouble absorbing the spreadsheet grid that spells out the shifts. Don’t laugh. Don’t yell. I’ll get it.

I’ll get there.

You remember Radio, don’t you?

Radio was that nifty gadget that broadcast news, entertainment, and music wherever you went. You listened to it in the kitchen while getting ready for work in the morning, and in the car while commuting. Radio was around for a long time. It documented the battles of World War II for the living rooms of America, bringing, for the first time, the horrors of war to the parents of the kids over there fighting as it was happening. That was astonishing. It had never been done.

Radio went on to bring us life as it happened. My generation was probably the last to gather round the on speakers on snowy mornings, cheering like mad when our school was declared canceled. We listened on election nights, to hear who was in or out in our town, too small for the big city media to care about. We listened to local talk shows during the day, to debate why our tax dollars were being used for this, instead of that. We listened on our commutes, to see if we should take I-93 or Route 128 to get to where we were going. It was a community.

Then Radio got greedy. It lobbied the government to get rid of the ownership rules, so a handful of companies could control all the stations in America. Then those companies tried to squeeze more profits out of stations, replacing local talk shows with syndicated shows like Rush Limbaugh. That made money. So then the companies pruned the newsrooms, arranging for two or three anchors to handle the news on multiple stations. There was no budget for street reporting. After a while, the conglomerates asked — why bother with local at all? Handing over those top of the hour newscasts to the national networks. As for music — well, that could be cheaped down, too. DJs were canned, and replaced with automation systems. What played on the classic rock station in Detroit was played on the classic rocker in New York.

After a while, Radio sounded the same in every town. It didn’t sound good. It sounded cheap. The same voices, up and down the the dial. The same subtle clicks as the computer shifted from canned music to canned announcements to commercials. After a while, the listeners stopped tuning in. Why bother, when nothing interesting, innovative, or exciting is going on? An iPod can give you music, without the commercials. And a person who slowly falls out of touch with the news no longer cares about it.

If this sounds familliar, it should. Now, this is network television’s story. TV: You’ve blown up the vast majority of your international news bureaus. This, when what happens abroad affects us back in the States in a way not seen since the 50’s. Your morning news programs have descended into something best branded as infotainment, where anchors undergo pedicures involving flesh-eating fish, and the Today show is essentially free entertainment for tourists on the streets of New York. You’ve made sure people don’t understand national and international news, cutting your own throat as the demand for hard news ebbs. People are getting their TV news dose from The Daily Show and The Colbert Report, shows that manage to be informative and mesmerizing. Not to mention — the questions asked of newsmakers on those shows are much more pointed than the softballs tossed on the nightly news. Your prime-time schedule is no longer built on scripted shows — instead largely consisting of a motley collection of characters willing to sell their souls for a few moments of airtime. NBC attempted the cheap road, sticking Jay Leno into the ten o’clock slot. The argument — from network brass — was that it may not attract a big audience, but would attract enough of an audience to make it’s inexpensive production worthwhile. We all know how that worked. Instead of holding onto a gem like the cop drama Southland, nursing it, and letting it build an audience; NBC let it go to TNT, where it has a devout following among a desired demographic. Your desired demographics are fleeing to cable — turning to AMC for Mad Men and Breaking Bad and The Walking Dead. They’re turning to HBO for Boardwalk Empire and True Blood. Viewers want to be surprised, and charmed, and thrilled, and swept up by emotion. You’re still giving them Survivor, which jumped the shark years ago; you’re still giving them Desperate Housewives, which hasn’t been fun for a couple of seasons; you’re still giving them The Bachelor, and pretending it’s a romantic thrill; until very recently, you were still giving them Two and Half Men, and pretending it’s funny. Your building is on fire, and you’re not listening to the smoke alarms. You’re losing your audience to the Internet, which offers entertainment far more original and fun than the stuff you’re putting on the air. You’ve lost your reputation as the go-to place for shows that trigger laughter and surprise; for news that isn’t lifted right off a politician’s press release.

Keep it up, Network TV, and it won’t be long before you’re on Skid Row drinking cheap gin from a paper bag, just like Radio.

Hi. Wow — I can’t believe I’m here. I never thought it would get this bad. But I’m here. I have to admit it.

My name is Eddie L, and I have a problem. I can’t turn away from Farmville. It calls to me. My herd of black sheep. The penguins I keep in a pen with my turkeys, even though I know that’s ecologically unsound. I ignore logic and believe I can grow both pomegranate and potato, even though they require opposite climates. I reap, reap, reap Nature’s digital bounty, even though I never rotate my crops and I know I am creating another Dust Bowl. I have abandoned logic!

So, I have come to you, Farmville Addicts Anonymous, for help.

Shall we begin?

I admit I am powerless over my addiction – that my life has become unmanageable

Like I said, my name is Eddie L., and I wish to acknowledge I am a Farmville Addict. I am powerless over the demon call of Farmville. I admit my life is unmanageable, because my life consists only of selling off my pen of pigs in Farmville.

I believe a power greater than myself can return me to sanity

Spock. It must be Spock. Spock was always the creature I turned to for guidance in this wacky world – before my motley collection of cows and horses and reindeer and ducks took over my life. I used to be a Classic Dork – not a Farm-obsessed freak. What would Spock, that pointy-eared lover of all that is orderly – say about Farmville? He would say it is not logical. I bow to you, Spock.

I am making a decision to turn my life over to a higher power

I am all yours, Spock.

I will make a searching and fearless moral inventory of myself

The only question here is what character flaw led me down the path into Farmville, a delightful place with a no-place-like-home farmhouse and a well-cared for chicken coop of happy hens. Why do I so desire to grow apple trees, yet have no desire to dirty my hands or actually sweat?

I must admit to a higher power, myself, and another human the exact nature of my wrongs

Spock, there is no doubt. I have behaved terribly. If I can say that to Spock, I can say it myself. I am doing so here. I would like to confess my sins to my wife, but I don’t remember what she looks like. Perhaps if I leave the Man-Room, where the computer is kept, I can find some wedding pictures to refresh my memory.

I must be ready to ask a higher power to remove these defects of character.

I am ready for my Mind Meld, Mr. Spock.

I must make a list of all those I have harmed, and be willing to make amends to them. I must make said amends

First off, there is the wife. I understand she lives, still, somewhere in this home. I’ve been told, via text message, that she wears earplugs all day long to block out the sound of Farmville music, which grates upon her very soul. Darling, the music will stop. And I will take you out! Perhaps to a — those places where they sell already cooked food for human consumption? I can’t remember what they’re called.

I also wish to make amends to your cat, Eleanor Roosevelt Rigby. I’ve been so obsessed with faux animals that I forgot we have a real living furry creature here at home! How exotic! I think it’s the poo. The Farmville animals don’t poo. Eleanor does. I don’t like poo. But I will learn to live with it. Poo is the price of love.

I will continue to examine my shortcomings and admit when I’m wrong.

Honey, you are always right. Always.

I will seek through meditation the peace and guidance that comes from a higher power

Spock, I beg of you to not abandon me. Perhaps Captain Jean-Luc Picard can offer some guidance. Please, make it so.

Having had a Dork Awakening through these dozen steps, I will spread the word to other addicts, and tell them there is help.

Spock will help you, too. Or perhaps your Spock are the Golden Girls. Hello Kitty? Or Curious George. It matters not. Take off the overalls. Turn away from Farmville. There are real, living creatures out there. You may be married to one of them! There is hope.

My name is Eddie L, and I am powerless over the lure of Farmville.

My upper arms ache all the way up through my shoulders. It hurts to sling a pocketbook over my arm. My hips hurt. My lower back hurts to the extent I can’t sit in the same position for more than ten minutes. My thighs? Fuhgettaboutit.

God Bless You, Advil. Because tomorrow, I’m going to do this to myself again.

I don’t look like a fighter. I’m female. I’m fat. My boobs are more suited to Playboy (trust me) than the ring. I’m clumsy—my body currently bearing the scars of a recent bike crack-up. I fall off curbs and down stairs. I have spatial problems and can’t quite remember what is left and what is right. I know jab and cross, through.

I started boxing a few years ago, as a joke. My husband was taking classes, and the instructor was offering a try-it-free session. He wrapped my hands, and I fell in love.

Throwing a punch felt very foreign, and very wrong, at first. I was the kid on the playground who usually got tripped or smacked or tortured. “Stand,” the instructor said, his gold teeth glittering under the fluorescent lights of the gym, “with your left shoulder forward, your knees only as wide as your hips.” Karim said, “bend those knees. Lower your head. Twist your torso. Now hit, baby girl. Hit.”

I threw like a baby girl at first, too, embarrassed that the heavy bag barely trembled, let alone swung, under the laughable non-force of my sad jab-cross combination. I kept at it, even when I was pretty sure the big boys with the barbed wire bicep tattoos at the gym were laughing at the fat girl attempting to become a fighter. “Don’t look at them,” said Karim. “You and me, we’re the only ones who matter here.” He’d put on the punch mitts and have me aim my punches at them, not getting pissed off when I accidentally hit him in the face. “That was a good one, baby girl!”

I didn’t get hit by an instructor until I’d moved on to Church Street Boxing, an old-fashioned boxing gym by the World Trade Center site with actual spittoons placed around the floor so the Golden Gloves contenders had a place to spit their blood after being hit in the mouth. Antonio hit me after I didn’t leap back to action at the sound of the bell, because I was engaged in conversation with a fighter with a nose as flat as the floor about the condition of Farrah Fawcett. “That bell goes, you go,” said Antonio, “or you get smacked.”

This was no girly kickboxing class. Church Street was another universe.

I thought I’d feel uncomfortable there, at Church Street. I have never felt more welcome at a gym in my life. Usually, as a chubby female not known for my grace, I feel like a pigeon among blonde birds of paradise with eating disorders. Not here. This was a land of broken noses, of dreams that had fallen in the ring and gotten right back up, of careers that had collapsed on the ropes and untangled themselves. This was a gym that kept a mop handy to soak up the occasional bloodstain. This was a gym where Golden Gloves contenders threw punches next to people like me attempting to learn the art; where taut 19 year olds readying for the featherweight title trained next to amateurs, like the 76 year old man who said he liked to feel powerful.

The trainers at Church Street coaxed the tiger in me to the surface. You must run, they said. You can’t last a round if you don’t run. So I ran. I put my fears of being humiliated aside, laced up my New Balances, and ran as far as I could. At first it was half a block. Then an entire block. Then two. I’m up to three and half miles now, which is nothing compared to a marathoner, but is a miracle for me. What astonished me is that I wasn’t a laughingstock as I ran down 35th Avenue in Queens, from my place in Jackson Heights to the edge of the Grand Central and back. The occasional truck full of landscapers or electricians would slow down next to me, the elephant lumbering along as the gazelles sprinted past. “Good for you, honey!” I’d get a thumbs up. The men doing maintenance at the housing project by the highway said they wished they had the motivation to run. When I said it wasn’t far, they pointed out a marathon is run one mile at a time. Wise men.

Now I do my rounds on my own back patio. I bought a stand up bag, the type you fill with sand, to beat up several days a week. I named him Karim, in honor of the man who introduced me to boxing.

I put on my t-shirt that says FIGHTING SOLVES EVERYTHING across the back, roll the bag, filled with about 200 pounds of sand and gravel onto the cheap faux grass carpet I bought to cushion it against the concrete, clip my portable Everlast round timer (three minutes on, one off) to the laundry line, crank up the headphones heavy on the gangsta rap, and get to punching.

I gave myself a boxing nickname, drawing on my New England roots and my history of covering snowstorms. The Nor’Easter.

The kids at P.S. 212 next door are fascinated by the Crazy Fat Lady Boxing Show. They were first drawn by the slamming sound of the bag rocking back from my cross, coming down on the concrete. They press up against the wrought-iron fence separating our properties, watching as I work through combinations and grunt with the force of the punch hitting the bag. I took off my headphones fast enough as the timer went off to hear one kid yell to his friends, “she’s got a TIMER!”

The people in my building have gotten used to my odd hobby. Some have had to learn about it the hard way—the building’s super once tapped me on the shoulder to say hi when I was mid-round. I came thisclose to clocking him. My husband knows to get my attention from the far side of the patio. The neighbors who live right above the patio are tickled, often leaning out the window and their pumping their fists. The man who lives next door stopped me in the street and said he couldn’t figure out what those long strips of cloth—my hand wraps—were, until he saw my gloves.

I love it when the sweat pouring from my head splashes against the bag. I love it when a kick ass song by NWA pops up on the headphones and I throw punches like the world is about to end. I love it when I have 20 seconds left in a round and despite my pain, I keep going. I love it when I’m rolling up my wraps at the end of 12 rounds and my shoulders ache like I’ve been battered myself.

Sometimes I beat up my husband. I’ve beaten up my boss. I’ve beaten up my editor and various co-workers. I’ve beaten up former and current friends. I’ve beaten up my mother. I’ve beaten up my father. I’ve beaten up Julie Gallagher, who made my life miserable in second grade. I’ve beaten up ex-boyfriends. I’ve beaten up the economy.

A remarkable thing happens when you’re able to do that. Another boxer at Church Street told me that people who don’t box don’t understand. It’s not about aggression. It’s about being able to leave everything you’re angry at on the floor, letting you be a calmer person.

Intellectually, I know I look like a four-star dork in my workout gear—complete with nerd sweatband!—when I box. I know I probably look somewhat silly, especially when I really get into it and start screaming my way through punches. I know it’s geeky to have the theme from Rocky on my boxing playlist. I know being proud of a strained shoulder and sprained wrist is a little ridiculous.

I don’t feel that way, though. I feel strong, and tall, and powerful. For the first time in my life.

The worst time to get stuck behind the Waterfall was right before a newscast. There I’d be, ready to go on the radio, and I’d be unable to do anything besides stammer as I’d reached for words. My program director would come in after one of those disasters and ask what the hell my problem was, and I couldn’t tell him.

The cornerstone of my life is writing. I’ve kept a journal since I was a girl. I write short stories and essays. I crank out buckets of copy every shift I work, breathing life into the clay that is radio, making people see, feel, taste, and experience a story they can’t see or touch. However, I couldn’t explain an epileptic seizure to my doctors. Those epilepsy junkies at New York Presbyterian told me, as I sat before them with electrodes glued to my head, that no one describes a seizure the same way. Fyodor Dostoevsky—one of Western literature’s finest scribes—was an epileptic, and wrote:

“For several instants I experience a happiness that is impossible in an ordinary state, and of which other people have no conception. I feel full harmony in myself and in the whole world, and the feeling is so strong and sweet that for a few seconds of such bliss one could give up ten years of life, perhaps all of life.

“I felt that heaven descended to earth and swallowed me. I really attained god and was imbued with him. All of you healthy people don’t even suspect what happiness is , that happiness that we epileptics experience for a second before an attack.”

Well, close.

Stand at the edge of a flight of stairs, let go of the banister, and look up. That sense of vertigo is the first sensation. Then the water begins to fall. It’s almost like I’m standing behind a waterfall, thick and fast, trying to reach through it, trying to speak through it. I can’t walk through the water; it would knock me down. I can’t hear you, as the water is too loud. And you can’t see the waterfall at all, so you have no idea what the hell my problem is.

When the strange feelings started in high school, I attributed it to my consume-nothing-but-Dexatrim-and-then-eat-dinner-with-the-family-diet. (NOTE: Not a good idea.) Sometimes the Waterfall came several times a day, always followed by a spectacular headache. Doctors said, it’s most likely a migraine aura. I dealt with it. I dealt with it when the Waterfall showed up while I was driving. I could feel it starting, and always had enough time to pull over. One time, it showed up at a job interview. I didn’t get the gig; I can only imagine the poor woman thought I was drunk. I’ve missed my stop on the subway because I couldn’t get up and make it to the doors. The waterfall showed up once while I was en route to work in Midtown Manhattan. I stood quietly at the intersection of 57th Street and Broadway, in my high heels and holding my pocketbook, until the water stopped. It was not an easy shift.

I dealt with it, until I awoke with a goose egg on my head and a broken toilet seat in the bathroom, not long after I’d moved to New York. “What the hell did you do?” I asked my now-husband. “You tell me,” he replied. “I’m not the one with a bump on my head.” “My insurance doesn’t kick in for another two weeks,” I said, “I can’t go to the doctor.” “You’re going,” he said.

Thus was triggered the yellow brick road of medical tests. Brain tumor? Some other form of cancer? Minor stroke? All would very rare in the case of relatively healthy 28 year old. Are you sure you weren’t drunk? High? Enough blood was taken to sate any vampire. The blood pressure cuff was wrapped on often enough to leave bruises around my bicep. The mystery persisted, until my now husband saw his future wife suffering a grand mal epileptic seizure in her sleep. Having lived alone for ten years, there had never been anyone around to witness me shaking in my sleep.

Seizures vary, a veritable rainbow of brain problems. My usual choice in seizures—The Waterfall—are classified as partial seizures, where I simply slip away for a few seconds. The Grand Mal, which I’ve only experienced in sleep and never fully remember, are the full-on shake, rattle, and roll routines. In both cases—and this is an extremely amateur assessment—the brain’s neurons misfire, skipping over the brain the wrong way, requiring the brain to kind of reset itself, like a computer that must be restarted. The partials are the sneaky little bastards, the unschooled not recognizing them as seizures.

My last seizure was a grand mal. I don’t remember the seizure itself, but, for the first time, I remember awakening from it. I was at my sister’s house in Massachusetts, and for some reason I insisted on working through the incredibly dizziness and standing up. I had to pull myself up using the ironwork on the dresser like a ladder to get from the bed to a standing position. The floor rolled like a ship; the room spun. I felt like I was going to be sick. But I stood. Worse came to worse, I probably figured my sister’s St. Bernard could drag me to help.

The treatment has been relatively simple and cheap — two pills, popped twice a day. It took some time to find the right dosage and only now, about seven years after being diagnosed, have I gone a year without a seizure. My memory has improved, because my brain isn’t going postal anymore.

All is not rosy. I’ve had to cut off my career at the knees, because I can’t work overnights anymore. Not good for a freelance broadcaster. But having a work schedule snake all over the clock isn’t good for becoming and staying seizure free. I’m going to have to give up the work I’ve always loved. I’m networking, building contacts, and moving towards public relations.

We don’t know where the epilepsy comes from. It could be genetic; it could have come from an old head injury. No one on either side of the family confesses to be epileptic. Then again, I didn’t know what the odd sensations were; perhaps they don’t either.

When I was last in the hospital for testing, with electrodes glued to my head so computers could capture my brain’s every move, New York Presbyterian’s head of epilepsy came to tell me they think they found the problem — neurons in the left temporal lobe that appeared to be behaving differently than the rest of the brain. I asked him to pause while I, ever the reporter, reached for my pen and notebook. He laughed.

“What’s so funny? I want to make sure I got it right,” I said

“I’m not laughing at you,” he said. “I’m laughing because I know I’ve got it right. People with left temporal lobe epilepsy will take notes on everything.”

I looked at the three notebooks I’d brought with me for my four day hospital stay. Well, I said, I am a reporter.

He said that cinched it. “People with your type of epilepsy usually work as writers.”

Yes, I made a note of that.