This spill…was special.

I knew I was in trouble after I’d spent ten minutes crawling around on concrete in the 25 degree weather, in the icy breeze blowing off the lake, looking for a tooth that may, at one time, have been in my mouth, without success. The part of brain not in crisis mode and still well-acquainted with my Girl Scout training said, “Say, I understand you’re concerned about spitting out mouthfuls of blood but do you think you should still be on the ground in icy weather when you might be going into shock? I mean, don’t you think your dentist could just make you a new tooth, if need be?” This is the part of my brain that likes to sprawl on a ledge overseeing the panic neurons as it relaxes with a glass of Riesling.

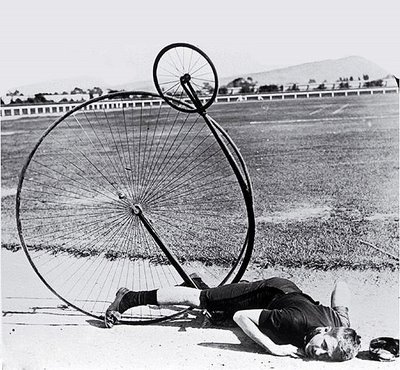

Falling is not a foreign affair to me. I fall constantly. I fall off of curbs, waiting to cross the street. I’m that person who falls on the crack on the sidewalk. I trip over tears in the carpet.I recently took a header down the stairs at JFK. I’m at the point in my life where I have accepted my limitations, where I refer to each spectacular crash as a “performance.” It is the closest I will ever get to being a ballerina.

Flushing Meadows is beautiful park in winter. It’s a park that doesn’t get much attention from the city, which is too bad; it’s home to the U.S. Open and Citifield (insert Mets joke here). It’s also a place of marvelous history, as it was home to the ‘39 World’s Fair, where television made its debut, and the ’64 World’s Fair, upon which Walt Disney based Epcot Center. There used to be a beautiful map of New York State on the floor of the World’s Fair Pavilion. The city has allowed that to decay, grass pushing its way up through the floor. More than forty years after the ’64 World’s Fair closed, the city finally landmarked the World’s Fair Pavilion towers, which carried visitors into the sky for a beautiful view of the park, Queens, and far away, the skyline of Manhattan. Preservationists say it’s too little, far too late, as the towers probably can’t stand much longer without major work.

Step away from the towers, and the steel Unisphere, and the empty reflecting pools that stretch to the Fountain of the Planets, and ride your bike over the ramp bridging the Van Wyck Expressway, and there find the joy you seek.

After summer packs up, the red leaves appear, the red-winged blackbirds pull out, and the water fountains are turned off, the bike path around Meadow Lake becomes an introvert’s dream. Every whisper of every leaf is amplified; every quack of every shameless duck looking for the (whole-grain!) mini-bagels I offer is as loud as a teenager’s car stereo. As autumn marches into fall, the bare branches crack the blue sky and the surf slowly freezes as it hits the shore, forming marvelous accidental sculptures of ice.

So I should have known better. I should have known even though the streets of Queens were free of ice and dry as could be, the water from Meadow Lake could play a trick on me. And it did.

I tried to control the bike as it slid, at about 15 miles perhour, letting go when I realized my hands would be better used for protecting my face than for guiding a bike. I went down on my face. The bike path was in extreme close-up as my sunglasses scraped the pavement. I felt the concrete in my mouth. And eventually, after a fun Slip-‘n-Slide event without the Slip ‘n Slide, I stopped.

“The first thing you must do,” said the reasonable part of my brain, “is get the hell up.”

When most people stand, it is a fairly instantaneous event. One thinks, I’d like to stand. And it happens. This standing took time. My right knee felt like someone was pressing a couple of dozen lit cigarettes on it. It buckled. My left hip didn’t quite want to accept the weight the knee couldn’t support. And so I picked up my bike, my loyal steed Blue Boy, and used it to support myself as I walked back 250 feet to where construction workers, in the bitter cold, were rebuilding the World Fair’s boathouse.

The brain is a funny thing. Mr. Reasonable, sprawled on his ledge watching the panic neurons, tried telling me I probably wouldn’t be able to hop the subway, go home, and rest it off. The panic neurons were screaming: You can’t take an ambulance! Are you nuts? It’s expensive!

I’d been obsessed with expense since my husband had been laid off from a major network newsroom four months before. I worried over every sponge, roll of paper towels, tin of cat food. I agonized over every bottle of dishwasher detergent.

The economic fall came in the midst of celebration. We were at Disney World, with my sister and her husband, celebrating my thirty-sixth birthday. I had never been to the land of enchantment and, as a professional cynic, found all the joy and glee somewhat overwhelming. I got a text from my former boss asking if my husband was all right. Then he checked his voice mail and got the message that, after ten years, he was out, along with a couple dozen others.

It is difficult to carry on in the happiest place on earth when one knows you’re going home to a place that is decidedly not.

My husband promptly dove into the pool of depression. I, being an anchor and reporter, am pretty used to getting canned. It happens all the time. New management comes in, decides they want their friend Fred on the air, and you’re out. My husband, working on the other side of the mic as an editor, had never been fired. He curled up in the fetal position, far away from any keyboards that could update a resume or work a list of contacts.

I got on my bike, and went to the lake. I found peace there, until I hit the concrete.

The kind construction workers who gathered around me point-blank told the panic neurons they were crazy. “Honey,” one said, not unkindly, “forget your mouth. Have you seen your knee?”

It was then I realized my right sneaker was bright red – the entire shoe – and that a steady, thick waterfall of blood was oozing through my unripped bike pants and onto the ground. As one guy called 911, another brought out their only “break chair,” and another pointed to the well-marked path of red that led me from the scene of the fall to where I stood now, waiting for the EMTs.

One of the guys took my arm and made me sit. Another propped my leg up on a lamppost. One grabbed as many paper towels as he could so I could try and stop the bleeding. All of them took their coats off in the sub-freezing weather for me. If they hadn’t done that, the doctors said later, I likely would have gone into shock, given that I’d already probably lost about a pint of blood. When the EMTs showed up, all of them threatened to punch the reporters who had shown up, too, because a report had incorrectly gone out on the police radios that a dog had fallen into the lake and firefighters were attempting an ice rescue. Then the construction guys took custody of Blue Boy, and stored him with their equipment until my husband was able to go get him. Who knew guys in hard hats could be so cuddly?

The EMT apologized before cutting off my fleece-lined winter bike pants, saying she knew how expensive they were (EIGHTY DOLLARS, DAMMIT). The tear in my knee was impressive. Six inches, wrapping around the kneecap, gaping open like a bright pink smile, exposing nerves and tendons. The doctors say the fact that the pants didn’t tear probably helped me immensely, as that held the wound together and helped with already copious blood loss. The doctors also seemed disappointed they didn’t need to do the emergency surgery they’d been told the patient en route from the park might need; if the impact had been half an inch higher, I would likely have shattered the kneecap.

One thing the doctors were thrilled about was the wound itself. So long! So wide! So jagged! How the hell did you do this? The physician’s assistant, Monica, told me she rarely got a chance to repair something so broken.

The twenty-one stitches was a victory, really. I set a record for the most-stitches-in-a-single accident – for both sides of the family. I was also the first female to rack up a black eye and a bruised cheekbone. I believe I am also the first in my family to require physical therapy for bursitis, which is the nerve damage I did to the hip.

I got texts and emails and Facebook messages after my husband was laid off, and after the fall. What surprised me was who didn’t follow through. A friend who regularly had crises with her asshole boyfriend, who would call her posse of girlfriends to her home to deal with her emotional breakdowns, bearing baked goods and booze, couldn’t be bothered to even e-mail me and see if I was all right. After the fall, I was told I couldn’t be in that bad of shape. Other alleged friends couldn’t be bothered, either, to check on us after the layoff, not bothering to invite us out when we couldn’t afford to drop a couple twenties on a night of dinner and drinks, when we had done the same for them when they were students. It was like we had a disease, and they didn’t want to get it.

Other friends surprised me. One couple, with a young child, invited us to their home regularly, and brought me a wonderful home-cooked meal when I couldn’t get off the couch without pain. Another swung by several times a week. Bad times are a kind of colander: the dirty water falls through, the beautiful fruit remains.

I was back up on my loyal steed, Blue Boy, two months after the accident. I brought the construction guys a big box of cookies. Every one stopped what they were doing, came over to see me, and gave me a hug. “We’ve been worried about you,” the foreman said. They were impressed by the scar. “I’ve been working outside all my life, and I don’t have one like that,” he said.

After a year of physical therapy on my knee, it still isn’t quite right. The tendons are still somewhat swollen, which my doctors say is normal. It could be years before that swelling recedes. But it’s getting there. I can now kneel on a hardwood floor without gasping in pain. I can run again, and I’m back up to two miles. I can box all I want. My knee has no problem with boxing’s constant crouch. It wasn’t all that long ago I called my husband to the door so he could watch me climb the stairs without the assistance of my cane, which I, under the influence of Percocet, had decorated to look like Steven Tyler’s microphone stand. “You have no idea how high you are, do you?” asked one friend, upon examining my artwork.

My husband, after eighteen months, finally landed a new job. And I’m still looking for a full-time gig, preferably in public relations or maybe even writing somewhere, as I look to leave broadcasting and earn a living in an industry that isn’t dying.

I like the scar. I like to wear skirts with bare legs and let that long line catch the sun. It inspires me to persistence, reminding me I can get up. It reminds of the husband who rushed from the house and let me bite his arm while a MD tried not to hurt me too much as she stitched me up, right over the exposed nerves of the knee. It reminds me that, in a city with a very cold reputation, there are still people who will help a stranger, give her their coats, and try to stop her bleeding.