Abdominals! We all have them and we all love them. Or, at least we love looking at them on other people. Like on Brad Pitt. Have you seen that dude’s abs? Shit man. I’m still in awe every time I watch Fight Club.

Wouldn’t you like to have abs like that? Sure you would! Maybe gender appropriate abs – some of the ladies might not want that über-ripped look – but surely you’d like to have visible abs of some sort. Some of you scoff! I can hear you now. “Pfffft, abs. My self-worth isn’t bound up into historical constructs of culture-specific beauty standards.” And I call bullshit. You and I both know that if we had a magical ab making button, we’d be pushing that sucker like a crack addicted rat in some Pavlovian science experiment, followed by a severe uptick in Absolute Time Spent Shirtless In Public (ATSSIP).

So let’s talk about abs. I don’t want to write about how to get them though; not today anyway. There’s a gazillion workout videos and how-to articles geared towards showing you how to work your abs. I don’t want you to mindlessly work your abs anymore. I want you to understand the thing itself. Part of the challenge I think a lot of folk have with developing their abs is they don’t know what it is they’re trying to work. “Abs” is a word that we all use, but most folk couldn’t define in any sort of concrete manner. We all know abs when we see them, right? You’ve got a vague, general sense of what abs are. But could you break it all down, spell it out in painful anatomical detail? Probably not. So that’s what we’re here for today. Before we worry about developing your abs, we’ve gotta know what we are developing first.

Your abs are not a single muscle

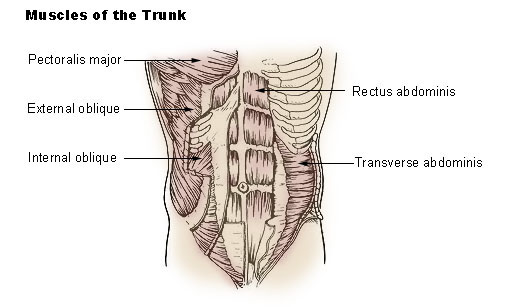

When we talk about abdominals, we’re actually referring to a group of muscles working together – and the break down might not be what you think. Your abdominals consist of six major muscles which can in turn be split logically into four “groups”. (There are also a host of smaller muscles involved in abdominal function, but for the purposes of this article I’m going to focus on the larger muscles of the abdomen.)

These major abdominal muscles are the:

- Rectus Abdominus

- Internal Obliques (2 each)

- External Obliques (2 each)

- Transverse Abdominus

A Little Background On Muscles

Before we get too far into how the abdominals work, it’s important to understand some basic principles about how all muscles work:

1) Muscles only contract. That’s right, I said it. Your muscles only provide pulling force, every single one of them. They cannot push. Keep this in mind as we work through how your abdominals work.

“But then how do I do pushups Mr. Smarty Pants?” you might say. (No, seriously, I’ve had that exact sentence uttered to me before.) Your body produces pushing forces by employing multiple muscles pulling against your bones in coordination to move your skeleton in the direction you want it to go.

Don’t believe me? Try this experiment. Right where you’re sitting, pick up your left arm and put it into a starting pushup position (upper arm parallel to the ground, elbow bent at a 90 degree angle, as if you were going to push someone away who’s too close to you.) Now, place your right hand over your heart. Push your left arm forward until it’s straight and your elbow is locked. Did you feel it with your right hand? You should have felt your left pectoral muscle contract (or flex) as it pulled your upper arm towards the mid-line of your upper body. That contraction, in conjunction with your shoulder and triceps muscles, is how you push with your arms. It’s all done with muscles pulling on your skeleton at key points.

2) Muscles have a starting point and an ending point. The starting point of a muscle is called its origin. The ending point is called its insertion. A muscle may have multiple origin and/or insertion points, but it has at least one of each. In general, you can think of the origin as the anchor point for the muscle, and the insertion as the point where the muscle pulls against your skeleton to produce movement.

Let’s take your pectorals again as an illustration. The origin for your pectorals runs along the length of your sternum up to your collar bone. A good visual example of this is the recently released shirtless pic of Anthony Weiner. This is the point that provides a solid foundation for the muscle to generate force from. The insertion for your pectoral is the upper part of your upper arm. This is the point on your arm where the pectoral pulls to produce movement. In this case, the function of the pectoral is to bring your upper arm towards the midline of your torso.

How Your Abs Work, ergo, How To Work Your Abs

Let’s take your newfound understanding of how muscles work, and apply this to your abdominals. Why do this? Why not just jump right into how to perform the perfect crunch? Because once you understand exactly what each abdominal muscle does – how it’s structured, where it starts and ends, what movement(s) its contractions accomplish – you can more effectively target that muscle for development in a vain pursuit of Brad Pitt like abs. Or whatever.

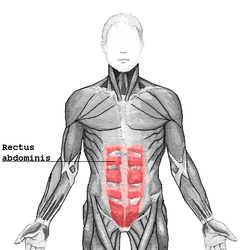

The Rectus Abdominus: This is the muscle everyone thinks of when we use the word “abdominals”. This is the muscle that produces the six-pack appearance. The rectus abdominus is a single muscle, not six smaller muscles. The bumpy, segmented appearance in the stereotypical six-pack is produced by the rectus abdominus bulging through bands of connective tissue that crisscross vertically and horizontally over the rectus abdominus.

The Rectus Abdominus: This is the muscle everyone thinks of when we use the word “abdominals”. This is the muscle that produces the six-pack appearance. The rectus abdominus is a single muscle, not six smaller muscles. The bumpy, segmented appearance in the stereotypical six-pack is produced by the rectus abdominus bulging through bands of connective tissue that crisscross vertically and horizontally over the rectus abdominus.

The function of the rectus abdominus is to bring your rib cage and your pelvis closer together. That’s it, pretty much. It’s the crunching muscle. The rectus abdominus’ origin is the pelvis, and its insertion is the lower edge of the rib cage.

External & Internal Obliques: The oblique muscles are located on either side of your torso, running diagonally in opposite directions from one another, from your pelvis to your rib cage. For the purposes of this discussion (this is a horribly gross oversimplification) you can think of your internal obliques as running diagonally from the side of your pelvis, forward to the centerline of your rib cage, in the direction of your sternum. The external oblique lays over the top of the internal oblique, and runs in the opposite direction – from the front of the pelvis to side of the lower rib cage in the direction of your spine.

The obliques have multiple functions, but again for the sake of simplicity, the obliques bring one side of your rib cage towards the opposite point on the pelvis. Think of an oblique crunch: on your back, you bring your right elbow to your left knee. Remove all the limbs, and really what do you have left? You’re pulling the lower right corner of your rib cage towards the upper left corner of your pelvis.

The obliques have multiple functions, but again for the sake of simplicity, the obliques bring one side of your rib cage towards the opposite point on the pelvis. Think of an oblique crunch: on your back, you bring your right elbow to your left knee. Remove all the limbs, and really what do you have left? You’re pulling the lower right corner of your rib cage towards the upper left corner of your pelvis.

The obliques accomplish this through the dual contractions of opposing oblique muscles. Remember that 1) the internal and external obliques run diagonally in opposite directions, and 2) muscles can only contract. This means that the right side external oblique works in conjunction with the left side internal oblique to allow you to twist to your left, and the left side external oblique works in conjunction with the right side internal oblique to allow you to twist to your right.

The obliques are also heavily recruited in providing stability to the upper body through static contractions.

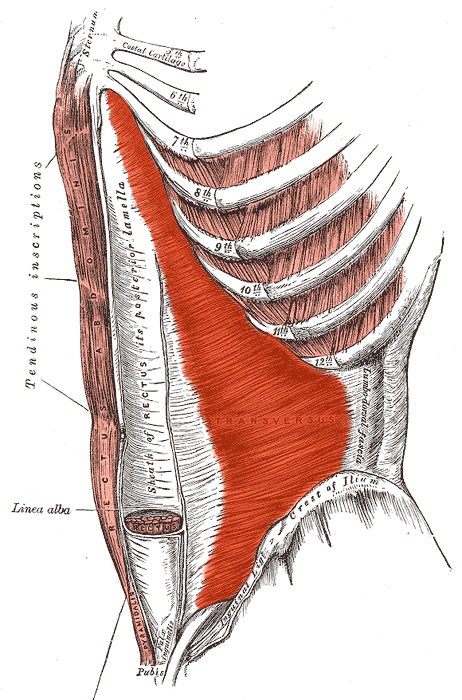

Transverse Abdominus: This abdominal muscle is the least sexy, but possibly the most important. It’s a long, wide, flat muscle that runs underneath the rectus abdominus and the obliques, encompasing the entire abdominal area. You can’t see it because it’s underneath the rectus abdominus and obliques, so it’s often not targeted for training by exercisers. This is a mistake.

The transverse abdominus is the muscle you use to suck in your gut or stick out your belly. Belly dancers use the hell out of their transverse abdominus. It’s hard (though not impossible) to isolate the transverse abdominus through isolation exercises such as crunches, as its main function is providing stability to the torso. Any movement where you contract and hold your abs in a static contraction most likely targets the transverse abdominus. The transverse abdominus is critical to creating the overall appearance of a flat stomach. You can be absolutely ripped, but if your transverse abdominus is weak and sagging it will produce the appearance of a rounded belly. Conversely, you might be carrying a bit of a spare tire around your middle, but a strong, firm transverse abdominus will go a long ways towards reducing the appearance of having a gut.

The transverse abdominus is the muscle you use to suck in your gut or stick out your belly. Belly dancers use the hell out of their transverse abdominus. It’s hard (though not impossible) to isolate the transverse abdominus through isolation exercises such as crunches, as its main function is providing stability to the torso. Any movement where you contract and hold your abs in a static contraction most likely targets the transverse abdominus. The transverse abdominus is critical to creating the overall appearance of a flat stomach. You can be absolutely ripped, but if your transverse abdominus is weak and sagging it will produce the appearance of a rounded belly. Conversely, you might be carrying a bit of a spare tire around your middle, but a strong, firm transverse abdominus will go a long ways towards reducing the appearance of having a gut.

I’m not even going to try to describe the insertion and origin points of the transverse abdominus. It does too many things. Go read the Wikipedia article if you’re curious.

That, in a nutshell, is how your abs work. Keep in mind that even though we’ve broken down each muscle on its own, they all work together simultaneously to provide movement and stability to the torso. If you’re targeting your rectus abdominus with crunches, you’re also working your obliques and transverse abdominus to a lesser degree at the same time. All exercises work your abs; some activities target particular abdominal muscles more than others.

One last caveat: Is this an oversimplification? YES! Please don’t reference this article in your next physiology term paper. You’ll fail. However, in part 2 I’m going build on this information to provide you with some concrete tips on how to target your abdominals (and other body parts) to improve the overall function and appearance of your abs.

(Other articles by allgoodpeople)

(Images from Wikipedia, AbsGirls, BuiltFit.com)