In the old days (from about the early-mid-1800s until the past 2 or 3 years) book publishing usually worked like this: the author wrote a book, and sent the manuscript to a commercial publisher, Random House, Faber and Faber, Akashic, there are thousands of them world-wide. The publisher employs professional editors to read the manuscripts and select (‘acquire’ is the usual verb used) ones with commercial possibilities. The author is then assigned an editor to work with to prepare the manuscript for publication.

The editor works with the author to clean up grammar, structure, and any other issues – weak characterisation, perhaps, or poor dialogue; bad organisation if it’s non-fiction. Works of both fiction and non-fiction are strictly fact-checked.

True story from one of my romance novels: “The hero puts his pro camera gear in the trunk of his Lamborghini. Do those cars really have trunks big enough for this?” I checked. Yes, they do.

The publishing house maintains an art department that designs a layout for the book, and puts together the cover art. The author has no say in the cover; no like, too bad. If you were Stephen King and made a big fuss, maybe, but other than that, forget it. Then the book is sent to a printing house. Generally, books for which there are big commercial expectations are printed first as hardcover. When the hardcover has been out for 6 – 12 months, a trade paperback is put out for sale. When sales of that format begin to taper off, the mass-market edition is sent out.

The printed and bound books are sent to the publishing house, which takes care of distribution. It sends out catalogues and, decreasingly, a sales force. The sales force visits bookstore buyers to convince them to put the books on their shelves and hand-sell them to their customers.

Any unsold books can, after a period of usually 6 months, be returned to the publisher for credit. The bookstore is responsible for shipping both ways.

The author is paid on the royalty system. Percentages vary, but are typically 5% or 10% of the cover price. Copyright for the title resides with the author; the publishing house has distribution rights.

If the title is successful, it can go into reprint, sometimes (but VERY rarely) for years and years. If it is unsuccessful, leftover copies go to a remainder house and are sold off for a dollar or two per copy. An exception to this are unsold mass-market paperbacks (pocketbooks) that have the covers stripped off and the blocks (pages) are shredded. The covers are baled up and sent back to the publisher as proof of it having been destroyed. It is illegal to sell a stripped book.

When the publisher decides there are no more sales to be had from a book, it is declared out of print and all rights revert to the author.

Now, on to self-publishing.

Still in the old days: a person writes a book. He or she then enters into a contract with what is called in the trade a vanity press, or subsidy house (the subsidy is the writer’s own money). The vanity press might call itself a publishing house, but it isn’t, because it offers no editing and no distribution.

The contract requires the client to have printed, at his or her own expense, a minimum number (often 1,000) of copies. The cost to print a trade paperback is $15-20, but that depends on a lot of variables such as size, illustrations, print run. So a typical self-publishing contract can extract $20,000 from the client.

Once the books are printed they are delivered to the client. That is the end of the vanity press’s involvement with the title. All distribution is up to the writer. Once you’ve pressed as many copies as you can on your friends and family, you hit the bricks-and-mortar stores to ask them to take some copies on consignment. Stores do NOT want to do this, because self-published books are an incredibly hard sell unless the author is well-known locally and is out there him or herself publicising the book.

Then along came the internet and stirred the industry up with a big spoon, nay threw the whole thing into a so-far-endless hurricane. The publishing options currently available would themselves fill a book.

Self-publishing is now much easier and cheaper, since many companies are offering e-book only, with no expensive paper printing. Some are offering a species of distribution. Probably some offer editing.

Additionally, print-on-demand options exist at a higher rate than e-books but still less than the required 1,000 copy run using older pressing technology.

Bricks-and-mortar bookstores have become as rare as elephants on the beach at Malibu. Traditional publishers are starting to assemble imprints (kind of a small publishing house within a larger publishing house) for self-publishing. Amazon and Barnes and Noble facilitate self-publishing. Teeny-weeny “publishing houses”, actually thinly-disguised self-publishing outfits, are springing up.

Once in a while a self-published book finds it market and hits the best-seller lists. Today we see a self-published trilogy, the Fifty Shades books, dominating this year’s lists. But such cases are very, very rare.

Self-publishing isn’t driven by the desire to write, but by the desire to see your writing bound and in print, on a bookstore shelf, and, especially, being read by other people. I confess I do not understand this drive, and look forward to reading what others have to say about it.

Amongst writers who have been published by traditional publishers, it’s considered bad form to call yourself an author until you’ve been edited. I’ve worked with lots of editors. They all made my work better. They have distance and perspective. They throw out that little bit of business I fell in love with but that just doesn’t work. They cut the paragraph where I got too interested in the research and slowed down the story. They made me add a brief piece of dialogue that explained the information that was in my head but that hadn’t, oops, actually made it to the page.

So here’s the key issue in the traditional publishing vs. self-publishing: did the manuscript go through the hands and head of a decent editor?

So here’s the key issue in the traditional publishing vs. self-publishing: did the manuscript go through the hands and head of a decent editor?

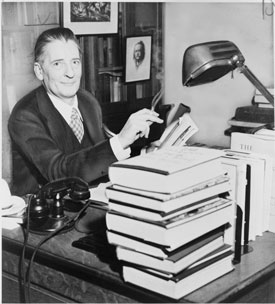

The gentleman in this photograph is of Maxwell Perkins, a hugely famous literary editor. Working for Scribners, he was the first editor to sign F. Scott Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald had been rejected all over town (New York) but Perkins saw the gold amidst the gross and worked long and hard with him on The Romantic Egotist, which you might know better under its final title, This Side of Paradise. He also worked with (i.e., kept the unstable writer’s nose to the grindstone) Fitzgerald on The Great Gatsby. Without this brilliant editor’s work we probably never would have heard of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Or Ernest Hemingway. Perkins had to struggle with his fellow editors at Scribner to convince them to publish Hemingway’s then-considered-scandalous first book, The Sun Also Rises.

Thomas Wolfe, similar story. Wolfe suffered sometimes from terrible writers’ block, and sometimes from one of the world’s most severe cases of writing long – Perkins cut as much as 90,000 words (about 500 pages) from the ms. for Look Homeward Angel.

Not that editors are infallible. Somewhere in New York is an editor, on whose wall is a copy of the rejection letter he sent to Alex Haley, for Roots. Meg Cabot’s book Princess Diaries was rejected 17 times. John Grisham: 12 publishers and 16 agents. Gone With the Wind: 38 rejections.

Here’s the most revered and repeated bit of advice from the publishing and bookselling industry: no one knows nuthin’. But I’ve read edited books, and I’ve read self-pub. Hands down, I prefer the edited ones.