I was a tomboy from the jump. While I played with boys and with girls, and had a female best friend, I detested “girls’ games” and girls’ things and hated going along with them. For example, I refused to play House unless I could be “the dad,” refused to play Office unless I could be “the [male] boss,” and preferred to play-act a Wild West shoot-’em-up, Holmesian detective drama, or high seas swashbuckling adventure rather than dress dolls. This is not an original story. A lot of girls are tomboys growing up. Many of them change their gender expression as they get older. Some don’t. Some people born with girls’ bodies and boys’ habits gradually discover that they will not be able to live authentically unless they change their bodies to be more visibly masculine. Some don’t.

I was a tomboy from the jump. While I played with boys and with girls, and had a female best friend, I detested “girls’ games” and girls’ things and hated going along with them. For example, I refused to play House unless I could be “the dad,” refused to play Office unless I could be “the [male] boss,” and preferred to play-act a Wild West shoot-’em-up, Holmesian detective drama, or high seas swashbuckling adventure rather than dress dolls. This is not an original story. A lot of girls are tomboys growing up. Many of them change their gender expression as they get older. Some don’t. Some people born with girls’ bodies and boys’ habits gradually discover that they will not be able to live authentically unless they change their bodies to be more visibly masculine. Some don’t.

I remember being perhaps five or six, after an afternoon of roughhousing that had devolved, standing in the driveway outside my house while a neighbor boy – with whom I had begun to share hours of “you show me yours, I’ll show you mine” as well as poring over his father’s Playboy stash – accused me of just wanting to be a boy. But you’re not, he said. You’re not a boy.

No, I don’t … that’s not true, I said, breathless with angst. I denied it because I didn’t know what else to say, but he was right. And the fight was over; he had won. Like all children, he was ruthless: he had found a tender spot and pummeled it. It was one of the first times during my childhood, but certainly not the last, when I recognized that, not only was I different – even among my friends – but that difference was going to be my weakness.

Equally vivid, though, is another childhood memory, of walking down the street with another neighbor to play at her house. I was wearing sneakers and a blue Oxford shirt tucked in to belted blue jeans like a miniature sitcom dad. My mother struggled with me about my clothes and haircut – “like a boy,” I insisted – but, eventually, mostly conceded the fight. She was not the type to cave in to unruly tantrums or special-snowflake syndrome; her anger and threats could be terrifying. I think, more likely, she was both worn out and wise from raising four daughters, of whom I was the youngest, and she knew that I wasn’t fighting just to test parental limits. She might as well have tried to make me right-handed as train me to be girlish.

Yes, she probably could have done either of those things. But she had a father whose left-handedness had been beaten out of him, and he was a rageful sonofabitch, or so I have learned. Maybe that had something to do with our eventual detente.

Ultimately, I was to dress in “appropriate” clothes for formal occasions, but otherwise wore boys’ outfits. And the occasional turtleneck covered in rainbows. I strolled next to my friend, attired in a chic mid-80s ensemble of red leggings and a red sweatshirt with a bright geometric pattern. An elderly man approached, walking in the opposite direction. As he passed, he smiled at us and said, “Little girl in the red, little boy in the blue.” And although my friend giggled in shock, loudly so that I knew the old man could hear it, I felt a frisson of delight that I had been taken for a boy.

When puberty approached, I took a couple of steps away from my masculine ideations. I wouldn’t say I was deeply insecure – I did well in school and was a talented athlete, and took pride in those things – but that age is a funny time, isn’t it? In retrospect I can see how apologetic and unsure of myself I was. I wasn’t desperate to fit in, but I didn’t want to stand out, either, so I began to grow my hair out, and dressed blandly. My style well into college was mostly about avoiding being seen.

Meanwhile, the summer I turned 14, I discovered Virginia Woolf, as well as the feeling that I might appreciate women, and girls my age, in a romantic way and, very obscurely, perhaps in a sexual way. I didn’t identify as a girl my age, though, or as a future woman. Nor did I identify any longer as a secret boy.

In Woolf’s writing in A Room of One’s Own, I found words for the feelings I could not articulate, and for what kind of self I aspired to express in my world: “[T]he mind of an artist, in order to achieve the prodigious effort of freeing the whole and entire work that is in him, must be incandescent, like Shakespeare’s mind. … There must be no obstacle in it, no foreign matter unconsumed.” Woolf later praises a (fictional) writer she has discovered, who “wrote as a woman, but as a woman who has forgotten that she is a woman, so that her pages were full of that curious sexual quality which comes only when sex is unconscious of itself.”

I simultaneously fantasized about being that kind of artist and ignored that Woolf’s advice here was about art-making — I took it as a manifesto for life. And although I could only incompletely understand what she meant about “that curious sexual quality,” her praise of the androgynous mind, burning pure, uncontaminated by the resentments and prejudices of sex and class, lit my own intellectual fire.

At the same time, striving for intellectual unsexedness made me ashamed of the schematic notions of gender that had driven my childhood self-expression. Especially once you realized it was all socially constructed – that the stories of masculinity I wanted to enact when I grew up were just that, stories – striving to be personally butch (a word I found repellent) seemed, well, gross. And childish, of course, since the last time I had felt free to express that masculinity was as a child. I was never going to be feminine, but I cultivated some stereotypically feminine virtues: sensitivity, gentleness, supportiveness, non-competitiveness. Self-denial, depression. Not coincidentally, I quit playing sports and rooting for sports teams.

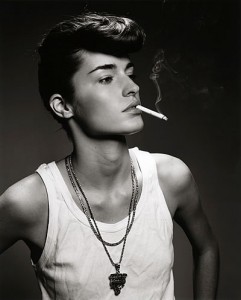

I don’t know how exactly this changed, but eventually, it did. Maybe, with the help of college-y kinds of conversations and college-y kinds of readings, I realized that if your ideas of gender difference and even sex difference are socially constructed, it’s all a performance anyway, no role more authentic or “true to life” than another. Maybe I was envious of other queer kids I saw at college; they seemed to have more fun being themselves than I knew how. Right before my 21st birthday, I cut my hair off.

My father was sad. My girlfriend was very sad. My friends were surprised, but almost all of them immediately said, “Wow, you look like … yourself.” And a day after my haircut, I went to dinner with my dad, ordered a beer, and was mistaken for a young man. The frisson was back.

That was over 10 years ago. As a grown-ass adult, I’m comfortable in my female body, with the idea that other people, men and women, may find my body (not just my “androgynous mind”) attractive, and also with expressing a more conventionally masculine appearance. I talk with my hands, cry at sappy movies, and gossip like a 13-year-old mean girl. I cut my hair military-short, grow it out into a Maddow, and trim it back again. When I want to look nice, I wear a tie. When I want to look really nice, I wear a tailored three-piece suit and a tie. I never feel more confident, at home in my own skin or more sexy, than in drag. I’m still working on stuff – dressing rooms make me break out in a cold sweat, for example – but I do not have to, and really couldn’t anymore, pretend about anything. Oh yeah, and me and sports, we’re on good terms again.

Being perceived as a dude is … something. I understand why it happens, because in addition to the masculine style, I’m taller than most women and virtually boobless. Nevertheless, it’s awkward on occasion, like when the bartender at a wedding doesn’t want to serve me – I gradually realize she’s convinced I’m a teenage boy – or when I’m the only person using the women’s restroom at 10 pm at an Alabama rest stop off I-10, and two drunk sorority sisters walk in and freak out . Or when I’m having breakfast with a straight female friend, and after attending us for a half hour, the middle-aged host calls me “sir” and my friend, who has never seen this in action, doesn’t know where to look. (Different people see different things: our waitress called us “ladies” the whole time.) Once I know I’ve been taken for a guy, I’m mainly concerned about whether my interlocutors will “find out,” and if so, whether they will be embarrassed, and eeeek. Like a nice girl, I am worried about their feelings. Rarely, every once in a while, it feels dangerous. But in truth there is often that thrill, that old (young) part of me that is just stoked at what just happened.

Being perceived as a dude is … something. I understand why it happens, because in addition to the masculine style, I’m taller than most women and virtually boobless. Nevertheless, it’s awkward on occasion, like when the bartender at a wedding doesn’t want to serve me – I gradually realize she’s convinced I’m a teenage boy – or when I’m the only person using the women’s restroom at 10 pm at an Alabama rest stop off I-10, and two drunk sorority sisters walk in and freak out . Or when I’m having breakfast with a straight female friend, and after attending us for a half hour, the middle-aged host calls me “sir” and my friend, who has never seen this in action, doesn’t know where to look. (Different people see different things: our waitress called us “ladies” the whole time.) Once I know I’ve been taken for a guy, I’m mainly concerned about whether my interlocutors will “find out,” and if so, whether they will be embarrassed, and eeeek. Like a nice girl, I am worried about their feelings. Rarely, every once in a while, it feels dangerous. But in truth there is often that thrill, that old (young) part of me that is just stoked at what just happened.

I can’t explain this feeling completely. It’s not the thrill of getting something over on somebody. It’s something else. It’s a little like the feeling of jumping on a trampoline, when your leap is at the highest point and you will imminently come down and bounce again: you’re not flying free, but for a moment you’re not earthbound, either.

Image sources: Kate, Michael Gross, Woolf, hottie