There are two countries that are always going to be linked in the Southeast Asia region due to their similarities, and the key choices that turned one into an economic powerhouse. Brunei and Singapore are the two smallest and wealthiest Southeast Asian nations, and have a currency interchange agreement. Sixty years ago, both set out to diversify their economies and become leaders in the region. The result is a real-world model lesson for developing nations.

1950s

In the aftermath of WWII both nations were hit very hard. Brunei’s oilfields had suffered massive damages from bombs and occupation by the Japanese, and the danger of the region led platforms to fall into extreme disrepair. It led Brunei to realize that it needed to diversify its economy away from oil. There had only been one field found around Seria, and the country was fearful oil would run out. In 1953, they started their first National Development Plan. The plan was to build infrastructure between the districts, provide hospitals and education to create a forward thinking workforce. Singapore was in awful shape following WWII, as the British boasted their fortress on the island could “withstand any attack.” That caused the Japanese to blockade the entire island and bombard it on a daily basis, until they surrendered. The island was in physical ruins during the 1950s with a huge homeless population. It was noted by the British Housing Committee that they were a disgrace to the civilized community. By 1959, the British had done little to solve any of the issues facing the small island, and granted both Brunei and Singapore their independence (more or less, Brunei was not fully independent until 1984, with the British taking care of all foreign affairs and defense officially until then).

1960s

In 1963, Singapore joined the newly formed nation of Malaysia, along with Malaya, North Borneo, and Sarawak. However, very soon after the new state was formed, Singapore began having issues due to its mostly Chinese population, and federal government regulations providing significant benefits for ethnic Malays. In two short years there were race riots and awful violence all over Singapore due to the tensions. By 1965, they were kicked out of Malaysia, causing Singapore to be one of the only countries that exists to have gained its sovereignty unwillingly. Lee Kuan Yew leader of Singapore famously said after the 126-0 vote to expel Singapore “For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I have believed in the merger and unity of the two territories.”

- Singapore in the 1960s

Brunei opted out of joining the Malaysian Federation, due to its rising success in the region. It had a GDP per capita nearly three times that of Singapore due to the discovery of a new oil field in the early 1960s. By simple statistics, Brunei was well ahead of the Lion City at this point in history (exports of 3,800 USD per person in Brunei vs 331 USD per person in Singapore), but oil was still well over 90% of the exports from Brunei. Many were predicting that the island of Singapore would fail with its new independence, huge unemployment, and lack of natural resources to fall back on. 70% of the Singaporean economy was based off the port, which could be taken away at any time by rival ports in Malaysia or Indonesia, should prices rise.

1970s

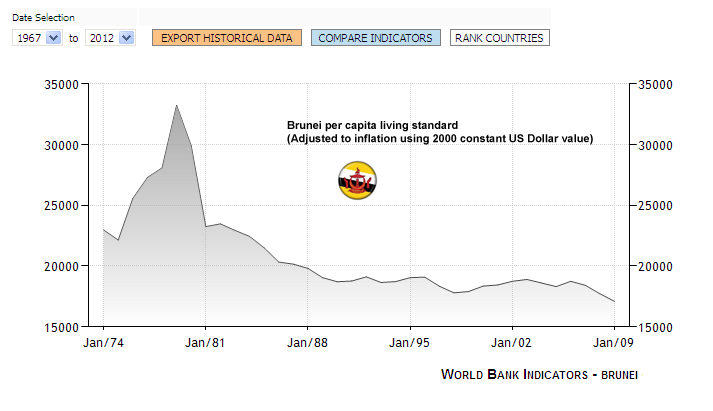

The 1970s was a good time for Brunei. Angered by Western support for Israel, Arab nations launched the oil boycott, leading to the 1970s energy crisis and oil price shock. This gave Brunei a windfall and awashed it with petrodollar, followed by a sharp rise in living standard. Just before the energy crisis in 1972, Brunei’s per capita GDP was $2,926, but in 1973 it blossomed to $6,971 – even more than Japan’s $4,157. By 1980, per capita in Brunei hit $25,538; the richest in Asia, compared to Japan’s $9,034 and Singapore’s $4,857. It was from here onwards the tiny Sultanate is to be forever associated with the word ‘rich’ and ‘wealthy’. It was also here that Brunei reached its greatest extent, never to have so wide a lead vis-a-vis Singapore and Japan since.

Today, the 1970s golden age and the fact that Brunei once had Asia’s richest GDP per capita is rarely mentioned in the country, perhaps due to embarrassment with its currently struggling economy. Sudden boom in oil revenues allowed Brunei to enter a period of rapid economic growth, with oil income greatly expended to modernize the state. In 1974, it completed the Brunei International Airport (7 years before Singapore Changi Airport in 1981). The country was able to connect itself with properly paved roads linking the port, oil town and the capital city, flourishing commerce and creating new wealth. Telecommunication service was greatly improved, the level of infrastructure was better than Singapore, and education rose sharply. The future of the Sultanate looked bright. Despite that, however, oil has given Brunei a sense of complacency. Other industries that once made up a considerable share of exports, like coal, rubber and cutch, were increasingly being neglected. Singapore was facing existential and survival threats that forced it to evolve, while Brunei was able to sit comfortably on its oil revenues.

Even though the 1970s were modern Brunei’s best times, it also solidified its reliance on oil and gas. After building factories en masse for 15 years, in 1970 Singapore finally got its high unemployment solved. There were some issues though. Unlike Brunei, which was wealthy enough to fund all developmental projects, the city-state was poor and could only afford to build flats and factories. Sorting housing crisis and high unemployment were the first priorities at that time, and infrastructure and education were left aside. In 1970, Singapore began to realize that no matter how many low-cost factories it had on the island, it is only a tiny nation with a small population, and neighboring Malaysia and Indonesia could always field a much larger labor force. The leaders began to realize the only way to succeed on a global basis was to have a highly-educated workforce and with investment from increasingly global corporations.

In the early 1970s, the island’s infrastructure and level of education remained poor due to the lack of economic growth since the end of WWII. Singapore then slowed the mass-construction of factories, and instead diverted most of their available funds to education, infrastructure development and upgrading existing facilities. The country though, wasn’t rich and the budget couldn’t support all the projects. Moreover, it would take at least one decade before a new batch of highly-skilled workers could be produced, something the city-state decided it could not wait on. Singapore decided that it wasn’t plausible to create a national workforce to stimulate its economy in any reasonable time frame, and appealed to foreigners, opening up the country to foreign investments and skilled foreign immigrants.

While Brunei was putting in place more protections for the ethnic-Malay population, the Singaporean leadership promised foreign companies what they loved to hear; that the government would be incorruptible, the government would respect capitalism and all foreign investments, no nationalization or seizure of assets would ever take place, and that Singapore would have regular and predictable law. The Lion City kept its promises and enforced them religiously. This differentiated the island with other third world nations, and successfully caught the attention of multinational businesses.

Foreign investments began to flush into Singapore. Knowing that they had gained initial foreign investments, and companies were looking to the region as a new market, Singapore moved on to offer tax concessions, simplified immigration procedures, tariff protection, exemption from import duties, and finally the lifting of foreign exchange controls. It resulted in the rapid industrialization of Singapore and greatly aided its next goal: attracting skilled foreigners. The foreign skill inflow was so massive that, by 2011, 40% of Singapore’s population were immigrants (27% non-citizens and another 13% foreign naturalized citizens). The Singaporean government adopted a business-friendly approach and actively adjusted to the corporate need. For example, in the 1970s, when high-tech industries abroad informed Singapore that they needed a local workforce with adequate technical skills, the city-state immediately launched free government training institutes which would train working adults twice a week for 3-hour sessions over a period of two years to meet the demand. Multiple companies started building facilities as a gateway into the growing Asian marketplace. Even without true offshore oil reserves, Shell and Esso constructed one of the world’s largest oil refineries in Singapore during the 1970s.

1980s

Stepping into 1980s, the energy crisis had calmed and oil prices subsided. The GDP within Brunei fell sharply, as the petrodollar fell. In 1984, the Sultanate became fully independent. There were 2 economic paths Brunei could take; the nation’s environment was ripe for rapid industrialization at the time and the capital was still available from the boom of the 1970s, but would require absorption of unskilled, foreign workers due to the tiny population of the wealthy sultanate. Allowing immigration on such a large scale in Brunei would have required a fundamental restructuring of the Country’s MIB (Melayu Islam Beraja: Malay Islamic Monarchy) philosophy that stressed the ethnic Malay must always remain the dominant race in the country. The conservative social and political nature of Brunei led to fears that an influx of foreign elements may disrupt the nation’s social customs, tradition and religion. Local Brunei Malay entrepreneurs were against international competition, and that kept the Sultan from opening the doors wide, as had been done across the pond. Plan for mass industrialization were dropped in favor of investing Brunei’s huge amounts of capital overseas. The Bruneian government invested in hotels across North America and Europe (which later merged to form the Dorchester Collection), the Willeroo Cattle Farm in Australia (which is larger than the country of Brunei), and various property assets across the world. Dependence on oil reserves continued.

Throughout the 1980s, Singapore’s industries had expanded to include electronic and computer manufacturing, shipbuilding and repairing, oil rig construction, chemicals, petroleum refining, and refining raw materials. As a result of intense, unchecked growth for years and skyrocketing wages, an economic recession hit the Lion City hard in 1985. In attempt to tackle the economic issues, the government quickly responded by freezing wages, lowering taxes, and reducing Central Provident Fund contributions. Singapore was able to work through its economic woes and have positive GDP growth by 1988. The lesson to Singapore’s economic bureaus provided the impetus to diverse into tertiary industries, concentrating on IT services, telecommunications, engineering, banking, finance, and medical.

1990s

With little industrial development, the Bruneian economy continued to slow throughout the 1990s. Increasing emphasis on MIB as a state ideology resulted in the banning of alcohol, nightclubs, and commercial pig farming in 1991. Singapore’s nominal per capita GDP surpassed the Sultanate in 1991. Though Brunei was still the richest in Southeast Asia in terms of PPP per capita, other ASEAN states like Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand were beginning to take note of Singapore’s success and model their governmental policies after the small island.

Brunei’s government sponsored another series of industrial projects in the early 90s in an attempt to move forwards after a decade of stagnation. A number of industrial estates were identified, including those in capital Bandar Seri Begawan and the Beribi industrial estates, followed by the construction of factories focusing on furniture, pottery, tiles, cement, chemicals, plywood, glass, textiles, food and electrical. Brunei’s push for industrialization however, came 40 years late – it was something Singapore had done in the 1950s. By that time the wages in Brunei were already considered too high, the industrial base too limited, and technological edge too low to compete with larger neighboring states in terms of scale and cost. Moreover, bureaucratic difficulties, poor coordination between government departments, and lengthy approval process deterred foreign investments, which mean the country couldn’t count on foreign multinationals to help develop outside of the oil industry.

Brunei began a period of state-led construction and initiated a huge amount of ambitious projects, leading to a construction boom to diversify from an oil-reliant economy to one that is service and tourism oriented. The restrictions on foreign workers were temporarily relaxed to allow large-scale projects and landmarks to be constructed, among them were a theme park, a magnificent hotel, and a huge power plant. Then in 1998, there was a financial collapse in Asia that wiped out almost half of Brunei’s foreign reserves. This collapse destroyed the construction industry within Brunei. The theme park was shut down, and is now dismantled. Unskilled foreign laborers were sent back home, leaving the economy with over 90% of its production related to oil revenues.

During the 1990s Singapore became classified as a Newly Industrialized Country, and was widely recognized as the third most important financial hub in Asia (Behind Hong Kong and Tokyo). The government actively sought after land reclamation initiatives and literally pushed the ocean back. Throughout the 1990s Singaporean businesses also surged from holding a 23% share of output in 1983 to 55% of the economy in 1998.

The financial crisis hit Singapore hard as well, but the government acted swiftly to minimize the damages felt by the populace. Rather than go back on their word and interfere with the private markets, they sponsored multiple construction projects and finished their metro system. Less than a year after the collapse, Singapore was back on track and ready to invest in the rest of the world. The government signed 13 free trade agreements with countries around the world, Singaporean interests would end up being the major investors in countries like Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Indonesia.

2000s

Within the 2000s Brunei refocused itself on social consolidation and Islamization. The country’s economic prospects were dim, and the government has focused on becoming the Muslim version of “A City upon a Hill.” Immigration visas are routinely denied, and work permits are extremely difficult to procure without advanced degrees and sponsorship from the country’s largest employer Brunei Shell Petroleum. Alcohol and tobacco are illegal, businesses are not allowed to be open from 12-130 on Fridays (Muslim prayer day), Sharia law has been passed and is enforced on the whole population. Brunei seems to have realized its economic woes, and rather than attempt to fix it, have shifted the focus for the country’s future. The goal is to become the Islamic center of Asia, and to be well respected by other Islamic nations. By mid-2000s, Brunei had a new national vision, the ‘Wawasan 2035 Negara Zikir’, which called for a pure Islamic economy by 2035. Rapid Islamization ensured, which includes compulsory Islamic studies for non-Muslim students. The central focus of its economic diversification is the ‘Brunei Global Halal Brand.’ It is not known how this would generate further revenues for the country as Malaysia and Indoneisa’s Halal brands are the largest suppliers of Halal food in the world. Participation of local Malay representative is a requirement for signing a contract with the government or Brunei Shell Petroleum. Brunei does not recognize natural born non-Malays (read: Chinese) as full citizens. There is a second class of citizenship for those born to non-Malays within Brunei that is causing many to migrate to Malaysia or Indonesia.

The 2000s was a period of great economic leap for Singapore. Its diversification into service industries materialized. Singapore not only had became the medical hub for Southeast Asia, it is now also the technological and communication hub in ASEAN, holding 50% market share of the region’s datacenter capacity. The country’s engineering capabilities is world renowned, with Singapore responsible for 70% of global offshore rig construction and 20% of the world’s ship repair market. The Port of Singapore was the busiest port in the world throughout almost the whole decade. One of the challenges faced by Singapore is the increasing sophistication of industries in neighboring states such as Malaysia and Thailand. Computer peripheral manufacturing moved into countries who are able to produce more, cheaper, and faster. Recognizing that the key to success for a small nation is not within the manufacturing sector, Singapore has shifted the long term focus to tourism and a knowledge based economy. After a forty year ban, casinos were invited to set up shop and it quickly became the world’s third largest gambling hub (behind Las Vegas and Macau). There is a huge focus on research and development within biotechnology and engineering for multiple industries. In 2010, Singapore was able to overtake the GDP of Hong Kong.

In 2011, Singaporean exports per capita were about 79,000 USD/yr, whereas Bruneian exports per capita were sitting at 25,500 USD/yr. After fifty years, Brunei and Singapore have completely switched places in the ASEAN region, and it really just comes down to exclusionary policies.

Sources –

- http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheigh … nomic.html

- http://emergenteconomics.com/2012/03/12/718/

- http://www.guidemesingapore.com/blog-po … -singapore

- http://www.edb.gov.sg/…/2000s.html

- http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Asia … ONOMY.html

- http://books.google.com.bn/books?id=z1c … frontcover

- http://library.thinkquest.org/C006891/reclamation.html

- http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Asia … STORY.html

- http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_h … ntent;col1

- http://www.ats-sea.agr.gc.ca/ase/5674-eng.htm

Images by the author except as noted below: