Lured by rumors of gold and ivory and in search of a new trade route to Asia, in 1471, the Portuguese first arrived at what is now present-day Ghana. What they found was an established gold trade by the existing inhabitants, who were members of the Fante ethic group. To participate in the gold trade, the Portuguese established a trading post in the present-day town of Elmina.

As their participation in the gold trade grew, the Portuguese decided to build a fort at Elmina to protect their interests against other European powers. In 1482, after coercing the Fante inhabitants to agree to its construction, the Portuguese began construction.

Building did not go smoothly. To build the fort, the Portuguese demolished villagers’ homes and attempted to quarry a rock with religious significance to the Fante inhabitants. The Fante responded by attacking the Portuguese, who retaliated by burning their villages. Despite tensions, the Castelo de São Jorge da Mina (Castle of St. George of the Mines), or Elmina Castle, was constructed in only 20 days.

The First European Trading Fort in Africa

Elmina Castle became the first permanent European fortification – and later slave trading post – in sub-Saharan Africa, which the Portuguese held for roughly 200 years. By 1500, Portugal imported around 22,500 ounces from gold from the “Gold Coast” each year. Soon, other major European powers, such as the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and England, built their own fortifications along the West African coast, also to participate in the gold trade. By 1700, there were at least 60 European fortifications within 300 miles of each other.

The establishment of such forts changed the relationship between the Europeans and the local inhabitants. Despite initial resistance, the Fante locals at Elmina were given protection against other tribes and allowed them to obtain certain goods more easily; however, the local people became more dependent on the Portuguese. Meanwhile, the European presence increased hostilities between local tribes, as the Europeans would respond harshly to tribes that traded with nations other than theirs.

The Door of No Return

By the 1700s, the gold trade gave way to trading slaves due to increased labor needs in the New World. Because the Portuguese refused to enslave the local people lest it interfere with the gold trade, most slaves were captured and brought from non-coastal areas. If they survived the journey to the coast, they were held at Elmina Castle or another fort. As the slaves were considered property, they were traded for goods such as shells, guns, mirrors, linens or beads. The men were then branded, while the women wore tags designating to whom they belonged.

Slave trading ships came every two months and required a certain number of slaves so that the trip would be profitable. In stark contrast to the luxury suites in the upper floors used by the Portuguese (and after 1637, the Dutch), the dungeons in which the slaves were held were virtually uninhabitable. Slaves were separated by gender and crammed into small stone cells, where they had no room to lie down or even raise their arms. There was no fresh air or light, save that from the small holes on the ceilings. Meanwhile, as slaves were very rarely let out of their cells, the floors were covered with fecal matter and other bodily fluids, so much so that the dungeon floors are now several inches higher than the original structure. Not surprisingly, many slaves died from disease; those that died were tossed into the sea.

Male slaves were chained during their captivity. Female slaves were not, but faced other indignities. Their dungeon was directly below the ammunition storage area, where gunpowder occasionally leaked below. Furthermore, the female dungeons were connected to the governor’s rooms via staircases. The governor would choose a prisoner, who would be bathed and enter the governor’s room through a trap door. Women who became pregnant were freed and housed at the fort.

Disobedient slaves, including women who refused to sleep with the governor, were severely punished. Many were taken to the courtyard and tied to an iron ball and chain, where they were left until either repentance or death. Insubordinate slaves were thrown into a special “condemned” cell to be forgotten until their corpse was thrown into the ocean.

When the slaves were to be placed on a ship to the New World, they passed through the Door of No Return. The door was an iron gate so narrow that people passed through it one by one. Slaves were then transported by rowboats to the main ship, where they were shackled to the floor by their arms and legs.

At Elmina Castle, roughly 30,000 Africans walked through that door each year.

Post Slavery

The Dutch held Elmina Castle for 235 years. As more countries abolished slavery, Elmina Castle was not the profitable trade center that it once was. In 1872, the Dutch transferred the fort to the British, who used it for military and police training. The local inhabitants, however, refused to acknowledge British rule; the British responded by razing the surrounding villages.

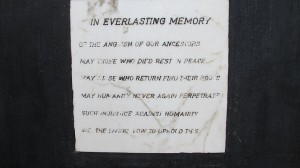

Today, Elmina Castle is a national museum in Ghana and an UNESCO World Heritage Monument, where tourists visit “in everlasting memory of our anguished ancestors. May those who died rest in peace. May those who return find their roots. May humanity never again perpetrate such injustices against humanity. We, the living, vow to uphold this.”

Image credits: Wikipedia Commons for 1, 3 and 5; Macjordangh’s flickr for 2 and BillBl’s flickr for 4.