Ephemera. Such a great word. Sorta sounds like the heroine of a bodice-ripper, non? “Lord Hunkley shook his fist at the retreating pirate ship and howled into the wind, ‘Ephemera! I will find you! Our love will never die!'”

But no. It means printed material that was never intended to last beyond its initial use. A newspaper, magazine, poster, a pamphlet, an auction advertisement, a bill of sale, a catalogue. Most of the print-run would have been thrown out once the auction was over, the concert had been given, the newspaper had been read.

Collecting ephemera is part of what is sometimes called the old-paper market. It’s similar to collecting rare books, except that books sit nicely on a shelf, but ephemera, which often consists of a single sheet of cheap paper, has to be filed flat, between sheets of permanent (no acid, no lignin, no sulphur) paper.

Single-sheet ephemera can be framed and hung on the wall, preferably out of direct sunlight, but it will inevitably be damaged by the light.

Fine-condition examples of ephemera can command very nice prices. A playbill for a production of Macbeth, the Theatre Royal, Monday 14 March 1831, Drury Lane, Covent Garden, London is worth $425.

An 1872 pocket map of Chicago, the first issued after the great fire, is now worth, in fine condition, about $2,000.

An 1831 pamphlet calling for “persons of good character” to emigrate to the Oregon Territory can go for $9,000.

A 1774 magazine containing the Boston Massacre oration by John Hancock, $12,000.

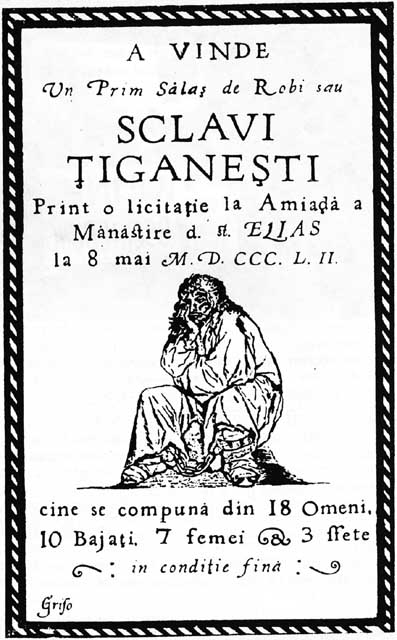

Slave bills of sale and slave auction advertising are part of a harrowing but important type of ephemera. If you visit Old South plantations, they often display old bills of sale for slave purchases.

Some examples of ephemera…