I can’t tell you the first time I heard her voice- all silk and honey and orange blossom water- gently emanate from my parent’s record player. It was always there in the background, caressing the air around us as my mother rolled grapeleaves, or had sweet mint tea with company, or chatted on the phone with my aunts as I played on the carpet. It was just part of the atmosphere of my home. It’s quiet Sunday afternoons after church. It’s holidays and the smell of roast lamb or turkey- my mom and my aunt Sona dancing dabke in the kitchen together as they cooked. It’s their fond memories of a childhood in Jerusalem and vacations visiting cousins in Boorj Hammoud (the Armenian quarter of Beirut). And this is something they share with so many people of the Middle East, Christian, Sunni, Shi’ite, Druze… Everyone loves Fairuz.

I can’t tell you the first time I heard her voice- all silk and honey and orange blossom water- gently emanate from my parent’s record player. It was always there in the background, caressing the air around us as my mother rolled grapeleaves, or had sweet mint tea with company, or chatted on the phone with my aunts as I played on the carpet. It was just part of the atmosphere of my home. It’s quiet Sunday afternoons after church. It’s holidays and the smell of roast lamb or turkey- my mom and my aunt Sona dancing dabke in the kitchen together as they cooked. It’s their fond memories of a childhood in Jerusalem and vacations visiting cousins in Boorj Hammoud (the Armenian quarter of Beirut). And this is something they share with so many people of the Middle East, Christian, Sunni, Shi’ite, Druze… Everyone loves Fairuz.

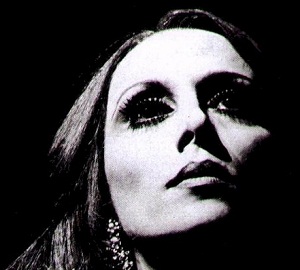

Fairuz was born Nouhad Wadi Haddad November 21, 1935, in the Village of Jabal al Arz, Lebanon to Syriac Orthodox and Marionite Catholic parents. Haddad’s talent was recognized at a young age and she came to the attention of Mohammad Fleyfel- professor at the Lebanese Conservatory who encouraged her to enroll. Let me rephrase that- who encouraged her conservative parents to allow her to enroll.

At the conservatory, she studied the classical Quranic recitation style of Tajweed. She was noticed by radio station owner and musician Halim el Roumi (father of Lebanese singer Majida Roumi), and Haddad was hired to sing as a chorus singer at the station. He later began to write songs specifically for her voice, and suggested that she change her name to Fairuz- Turquoise.

She was later introduced to the songwriting duo of Assi and Mansour Rabhani, and the rest is history. Her first major hit came with ‘Itab, written by Assi Rabhani, whom she later married, but after that first smash her career exploded.

Now I realize that her popularity is culturally specific, but allow me to give you an idea of just how beloved she is in the Middle-East. There are only two female singers in Arabic music whom I know to have reached this kind of popular Zenith. Obviously Fairuz is one of the two. When the second of these two died, her funeral procession shut down Cairo. Seriously.

There were more people at Oum Kalthoum’s funeral then there were at Anwar Sadat’s.

When it’s Fairuz’s time to go to her gig at the good Lord’s concert hall (knock wood), I imagine Beirut will be similarly flooded with the bodies of tens of thousands of mourners.

So when I say her career exploded, I mean soon found her recordings played in every non-wahabi household from Cairo to Baghdad.

After her initial success with ‘Itab, Fairuz, gave her first major live performance at the Baaelbeck International Festival, and began touring heavily, starring in the Rabhani Brother’s light operas. These operettas were the Rabhani Brother’s bread and butter, and several of them were adapted into films, or recorded and later televised.

Probably the most well known of these adapted musicals is Bayya’ al-Khawatim (The Ring Salesman).

I was lucky, and found the entire, full-length movie for those of you who love Arabic music and corny musicals from the early 60’s. Heaven bless the patient copyright infringer who uploaded the whole damn thing for our enjoyment, because I frankly was worried about finding film clips.

The Ring Salesman (like so many musicals) is the story of young love and elder’s expectations:

“This light musical operetta is about a small village where the young people are preparing for an annual festival in which many will choose spouses. The mayor of the village, who has a niece named Rima, decides that the villagers are too bored and need to have their imagination stimulated. He invents and tells stories about a fictitious person named Rabi’, describing him as an enemy of the village. Then two idlers in the village start to steal, damage property…while putting the blame on Rabi’. Things look even worse when a tall, strong stranger enters the village, says that his name is Rabi’, and asks Rima where he can find the village’s mayor. But it turns out that he only wants to ask the mayor’s permission to sell engagement rings and jewelry to the villagers. The story ends happily as the two idlers are exposed and forced to marry girls chosen by the mayor.”

Yes, I know. That last sentence makes absolutely no sense, but that’s the plot, as described by a native Arabic speaker. Make the lazy thieves marry two women of the Mayor’s choosing? Oh, I’m sure their fathers would be THRILLED about that. It reminds me of the butler pitch from Seinfeld. But, really Rabhani and Fairuz’s works all require a healthy dose of suspended disbelief.

Most of Rabhani’s musicals take place in small Lebanese villages and portray an idealized small-town lifestyle that hearkens back to an imaginary time when people’s problems were simpler. Let’s not fool ourselves. The Middle East always has been and always will be fucked- plagued with geo-political maneuvering and leadership that treats ethnic and tribal groups like chess pieces with a pulse. But that simplicity is certainly part of Fairuz’s appeal. Sentimentality for how life appeared to be as a child or adolescent is especially strong during a time of political turmoil, and Lebanon’s political and ethnic tensions coupled with the resentment over the Palestinian refugee situation was just about to boil over when majority of these musicals were being produced.

That’s not to say that Fairuz and the Rabhani Brothers never got political.

Safar Barlik (The Exile) deals with the Lebanese experience shortly before WWI, as Ottoman troops invade Lebanese villages and confiscate farmland to feed Ottoman troops. Those who resisted the Ottoman rulers were forced into Exile. (Again, I have to thank the industrious pirate that uploaded this, as again, this is the full movie.)

Many would consider Sanarjiu Yawman to be a sympathetic nod to Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon. Well even if it wasn’t Rabhani’s intention, it’s too late now, because it’s essentially the theme song of Palestinian self-determination and an anthem for the refugees of Palestine scattered far and wide across Europe, the Americas, and the Middle East, including the Occupied Territories, of course.

And then, well, and then there’s the Lebanese Civil War…

I think I’ll let the lyrics speak for themselves:

Hawa Bairut (The love of Beirut)

They put up road-blocks

they dimmed all the signs

they planted cannons

they mined the squares

where are you love

after you we became

the love that screams

we became the distances.

For the happy days we longed

the days of staying up on the road

the long walks

the rendezvous at the old restaurant.

O love of Beirut

O love of days

They will come back Beirut

the days will come back.

It is the second summer

the moon is broken

is it true you may forget me

my defeated love

I went back to my house

my house I didn’t find

only smoke and twisted beams

no rose and no fence.

During the war, Fairuz and the Rabhani brothers wrote numerous songs decrying the violence, and advocated for community peace. “Petra”, a political satire set in the famous city carved into the cliffs, deals with a king and queen who lose their daughter after she is kidnapped by the Romans, with whom they are at war. It was shown on both sides of the divided Beirut, which was unheard of at the time.

More recently, Fairuz declined the invitation to perform the Western Good Friday Funeral Mass, as is her tradition, due to ethnic and civil tensions following Prime Minister Rafik Hariri’s assasination, stating that she would, “not sing to a divided people.”

Fairuz’s personal life wasn’t exactly the bed of rose petals her films championed. In 1972, her husband Assi Rabhani suffered a brain hemorrhage. As his mental health deteriorated, Rabhani and Fairuz agreed to discontinue their personal and professional relationships. Fairuz’s songwriting and production was handed over to her son Ziad Rabhani. Assi died in 1986, and to m his funeral procession, all sides of the Civil War declared a cease-fire and opened up the roadblocks to allow mourners to pass. She is still embroiled in copyright disputes with Mansour Rabhani and his heirs.

Fairuz is still a very active musician. At 76, she still performs to enormous audiences, most recently in June of last year in Amsterdam at the Royal Carre Theater and a five concert series last December at Platea Theater in Salhel Alma, Lebanon.

Fairuz is widely beloved because speaks to our better nature. To patience, and love and innocence. To tradition, and ingenuity, and flexibility. She and her ex-husband and brother-in-law, managed to bring together the tribes and the various ethnic groups of the Middle East into one room, to listen as one body-a fanbase- to a beautiful message carried by a singular voice.

I’m Writing Your Name

I’m writing your name my darling

On the old poplar

You’re writing my name my darling

In the_ sand on the path

And tomorrow it will rain

On the wounded stories

Your name will remain my darling

And my name will be erased

I talk about you my darling

To my the people in the neighborhood

You talk about me my darling

To a spring of water

And when they burn the midnight oil

Beneath the lamps of the_ evening

They talk about you my darling

And I am forgotten

And you gave me a flower

I showed it to my friends

I put it in my book

I planted it on my pillow

I gave you a vase

You didn’t take care of it

And you weren’t concerned with it

And so_ the gift went to waste

And you tell me you love me

You don’t know how much

That you still love me.

You need to buy this:

and this:

and this:

and of course this:

Fairuz has an extensive discography, which you can find here.