City politics in the city of Toronto has been very interesting this week, since a vote Wednesday in Toronto’s city council led to the collapse of the mass transit plans of Toronto mayor Rob Ford. Ford had hoped to concentrate on expanding subway service in Toronto, opting against surface light rail; Ford’s opponents, led by Toronto Transit Commission chair, city councillor, and former Ford ally Karen Stintz won a vote that would instead restore plans for surface light rail routes. Mass transit has been an emotional issue in Toronto, and this vote aside the controversy is likely to continue.

Why? Honestly, a big reason for the controversy is that Toronto isn’t really a unified city on the ground, that Torontonians live in a new city that remains profoundly divided–is arguably becoming more divided–on lines of geography. Yes, the City of Toronto was incorporated back in 1834, but the modern megacity of some 2.7 million people dates to 1998.

Before 1998, the City of Toronto was a much smaller municipality, located in the south-central area of the modern megacity. In 1954, to provide a framework for regional planning as Toronto’s suburbs flourished post-war, the city was federated with five other municipalities in a regional federation known as Metropolitan Toronto. The component municipalities retained their own municipal institutions to cover purely local issues like municipal planning, with Metropolitan Toronto managing facilities that the different municipalities shared in common like transit, housing, and parks.

Metropolitan Toronto worked well enough for a time, but as the 20th century progressed and the Toronto conurbation expanded beyond the confines of Metropolitan Toronto–the Greater Toronto Area referred to by planners has ten times the surface area that Metropolitan Toronto did–its perceived utility shrank. In the 1990s, as governments throughout Canada and across the world tried to economize on government expenditures, the right-wing Ontario provincial government decided to save money by getting red of Metropolitan Toronto’s component municipalities and making a single City of Toronto.

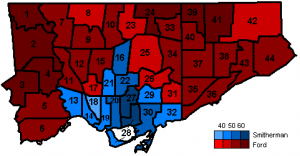

The problem with this? The inhabitants of the megacity didn’t want this unification, and the city remains sharply polarized on the old borders. Look at the results of the 2010 election.

This division also occurred in the 1997 and 2003 mayoral elections. It would be reasonable to say that sharp contrasts endure, between a downtown core that has been strongly in favour of greater government investment in building a dense city of Toronto strongly inclined towards New Urbanist philosophies with a suburban periphery that’s much more skeptical about these projects and skeptical of waste.

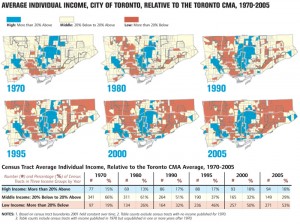

Numerous studies have highlighted economic and demographic divisions, too, with the relatively more white downtown being relatively richer than the relatively declining and heavily immigrant peripheral regions of Toronto. This division has defined city politics. In the most recent election, Rob Ford defeated his downtown opponent George Smitherman through his appeal to the suburbs, promising to make city government more efficient (despite more recent studies demonstrating that the city government was already efficient, that there was not in fact a “gravy train” as Ford had said) and to extend to the suburbs the subway service that would mark their inclusion in the city (although subway construction is considerably more extensive than the surface light rail plans he rejected, the suburbs arguably don’t have the density necessary to support subways, and the money would be better spent on light rail which would transport more people more efficiently anyway).

There’s a non-trivial amount of mutual alienation, and it’s worrying. Toronto writer and flâneur Shawn Micallef picked up on this when he reported on his visit to a Ford election rally. Left-wingers and downtowners don’t understand suburbanites and often substitute an ill-judged contempt for that.

An odd thing happened as I was Tweeting: at first, online followers were in the spirit of our fun and somewhat gonzo act, but when it became clear we weren’t going to Tweet about how awful and, as Howard Moscoe might say, illiterate Ford supporters are, I started to pick up some hostile reactions. By simply going to Ford’s BBQ, and not thinking they’re freaks, it seemed to some folks on Twitter that my companion and I were endorsing him. Neither of us was toeing the narrative line we’ve been told to believe about Ford supporters since he started to run. Now that he’s leading, that narrative is dangerous.

The Ford supporters at the BBQ reminded me a lot of the working-class crowd I grew up with in Windsor: same “regular folk” but here in Toronto without Windsor’s long tradition of organized labour involvement and NDP voting to swing general sentiments in a leftish direction. Reader’s Digest by the toilet, white wine cut with 7UP and wood-panelled basements — this is comfortable territory but not highly politicized. Money is always an issue, though, and the whiff of waste isn’t taken lightly. Ford’s tapped into this and swung people who down south would be called “Reagan Democrats.”

That’s why the continued mocking of his supporters, his issues and his weight have given him momentum. His simple message resonates with these voters, people who aren’t radical and likely wouldn’t identify as right wing. It’s a kind of apolitical politics. In Windsor, the left filled this space. In Toronto, the roles are reversed. Ford’s campaign is beyond facts, now, which require smart thinking. The rise of the Ford Nation is as much a communication problem of the progressive side of Toronto as it is Ford’s regular-guy charisma. If his opposition doesn’t understand this crowd, we might have four years of Ford Fests ahead while we figure out how this all happened.

Writing at regional blog Torontoist at the other end, Hamutal Dotan warned about and criticized the attempts by Ford et al. to invoke suburban grievances against the downtown core, to claim that downtown Torontonians are willing to marginalize the peripheries with unrealistic schemes.

What will come of all this? I don’t know. I’ve lived in Toronto for the past eight years and the amount of polarization within the city has been growing: political, economic, demographic. Toronto has positioned itself–been positioned by others, too–as an ideal of the global city, as a community that has responded to the challenges of globalization with aplomb. How much longer can it continue to do this if its internal divisions remain as notable as they are? Can they ever be bridged at this point? I wonder, and fear.