The following is a rundown of the methods employed by an experienced director coaxing an unwilling performer sulking in a walk-in closet to film a four-way adult scene.

The following is a rundown of the methods employed by an experienced director coaxing an unwilling performer sulking in a walk-in closet to film a four-way adult scene.

Filmed incorrectly, the scene might win a Razzie. Get it right, and the rest of the film would click into place.

Pope [the film’s producer] found two porn actors to play the other participants. The woman walked through rehearsal completely naked, bragging that she refused to conform to porn’s norms and shave her pubic hair. Lohan freaked out.

[…] [She] was uneasy working with porn stars and actually, truth be told, was uneasy working with Deen.

Schrader [the film’s director] lost it. […] He thought of sending everyone home. But then he realized that there was one thing he hadn’t yet tried. He stripped off all of his clothes. Naked, he walked toward Lohan.

“Lins, I want you to be comfortable. C’mon, let’s do this.”

Lohan shrieked.

“Paul!” […]

But then a funny thing happened. Lohan dropped her robe. Schrader shouted action, and they filmed the scene in one 14-minute take. About halfway through, Lohan looked directly into the camera and flashed a dirty, demented smile at Schrader. He smiled back.

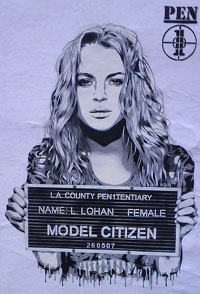

This a sample of Stephen Roderick’s observations behind the scenes of the upcoming film, The Canyons, and the long shot decades-seasoned director/screenwriter Paul Shrader takes on his two stars: James Deen, porn unicorn; and Lindsay Lohan, an actress whose brief and brilliant moment as the Next Big Thing dissolved into tabloid fodder, (“There have been house arrests, car crashes and ingested white powders”, Roderick notes coyly), forgettable box office failures like Georgia Rule, and desperate-seeming photo spreads.

I thoroughly enjoyed Mean Girls and found Lohan likable and funny as its heroine, but ultimately what I saw in her climax and extended downfall was less the tragic waste of a magnificent actress than a drunk-driving walking, talking example of everything that could go wrong with being groomed for show business from babyhood. Nevertheless, Roderick’s feature for the New York Times is worth a read for its plainspoken chronicling of how the sausage gets made and his miraculous ability to present Lohan as equal parts maddening and undeniably skilled (or at least technically savvy) in her theoretical craft:

The light faded while Lohan gave a running commentary on how the scene should be played, which happened to be the exact opposite of what Schrader wanted. She finally stopped talking and turned to the director.

“Paul, how do you want to play this?”

Schrader sighed.

“I was hoping to direct the scene, but it’s apparent that you’re not going to let me. Let’s skip it. It’s too late, the light is lost.”

Pope rushed in and put his arm on Schrader’s shoulder.

“Let’s give it a shot.”

Miraculously, the cameras rolled, and all the tension, all the ego, all the incoherence exploded into the film’s most riveting scene: Deen, cold and evil; Lohan, vulnerable and afraid.

All that remained was to get a close-up of Deen touching Lohan’s face with a blood-streaked finger. […] Most actresses would pop in some Visine to well their eyes with tears and be done with it. Lohan went back to her room, and everyone waited.

I was standing by her door, and soon I could hear her crying. It began quietly, almost a whimper, but rose to a guttural howl. It was the sobbing of a child lost in the woods.

Shrader’s relationship with Lohan—firing her temporarily when he finally tires of her erratic behavior, rehiring her when it’s clear that no one can play the part better, and coddling her, resigned to the hassles, for the duration of shooting–reveals a director who sees the duel between his actress’s personal hang-ups and charisma as the catch that would make or break the film.

James Deen is somewhat neglected in the piece, but not only does he come off the more professional of the two actors (except for a day during shooting when he cut his losses, stopped waiting for Lohan to show up, and went to Burbank to film porn), but an arguable saint for stomaching Lohan’s moods, inferred from recently leaked audio of the actress insulting him. Roderick only mentions Deen’s sense of frustration with his costar briefly.

Will this film help Deen on the road to becoming the next Robert Pattinson? Can literati envywhore and Twitter mean queen Brett Easton Ellis reinvent his profile through screenwriting, or will this film be a dud like The Informers? Is there really any reason to see Lohan as anything more than a cautionary tale of frenzied early fame and the perils of moving from childhood success into adult longevity?

…Can you imagine a film with Lindsay Lohan behind the camera?

Whatever the answers, if there’s anything fascinating about her, it’s that Lohan–hyped, trashy starlet or diamond in the rough–has endured in popular culture for an audience preoccupied with youth, its inevitable crash and burn, and redemption, especially if the road back starts someplace strange and low.

Image via Flickr