A frequent sighting in central Colorado’s festivals, farmers’ markets, and Earth Day events is John Anderson, “the worm man.” Happy to teach both children and adults the benefits of vermicomposting(worm composting) his mantra is “starve a landfill, feed a worm.”

I had the honor of meeting Anderson in person at a permaculture certification course at the Lyons Farmette in the spring of 2010. He showed up in his refurbished 1975 Dodge ambulance, now called the “wormbulance,” to teach us the finer points of vermicomposting.

“This is my life, not just my business,” says Anderson, 57, a master composter and founder of Fort Collins–based Garbage Busters, a traveling resource for all things worm. “So much of the stuff that goes into the landfill is organic matter,” he says. “If it came from the land, it should go back to the land without poisoning it. Worm composting is an ideal way to make that happen. Waste is not waste until you take the action to waste something.”

A view of Anderson’s operation

A view of Anderson’s operation

Anderson has played a significant role in reducing the organic matter going to waste in the landfills servicing Fort Collins, Colorado. Now at least 25% of that discarded material is going to Anderson’s worm farm, where he sells compost and worms or barters them in exchange for work. He is happy to share his knowledge of composting with anyone with a desire to learn.

He first hot-composts large quantities of raw materials in giant tumblers. “You could put a whole cow in there,” he exclaims in his Minnesotan accent. The bacterial action quickly breaks down organic matter into bits more easily digested by the worms.

Compost tumbler for preparing worm food

Compost tumbler for preparing worm food

Next the partially-composted organic matter is offered to the worms, which are arranged in long windrows covered with carpet or worm bins made out of converted old refrigerators. The key to success with worms in Colorado is keeping the compost moist, but not soaking wet. The worms are highly adaptable and aren’t too picky about their environment. According to Anderson, though, they will let you know if their surroundings aren’t to their liking. “I got a stampede once! The bin got too hot and they were practically jumping out of it. You can’t believe how fast they can move.”

These are not just your everyday earth worms (lumbricus terrestris) but are a smaller genus known as red wiggler worms (eisenia feteda) which live close to the surface and can consume half their body weight in organic matter daily. It is believed that humans have partnered with worms for conversion of waste back into fertile soil for thousands of years. This symbiosis allows humanity to renew the soil and continue to enjoy good produce from the same land without depleting the soil. One could argue that humanity cannot continue to feed itself without this partnership.

Size comparison of red worm and nightcrawler

Size comparison of red worm and nightcrawler

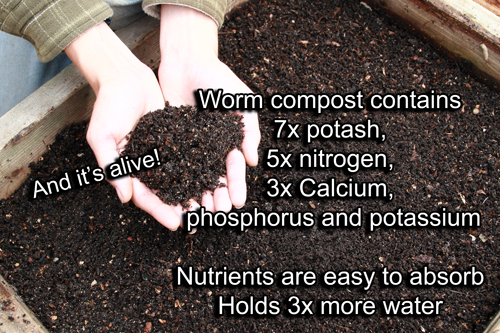

The end result of the worms’ digestion is called castings and is considered the “black gold” of organic gardening. Because of the symbiosis of worms and beneficial bacteria, the worm castings are not only far more concentrated in nutrients than plain soil, they also contain beneficial bacteria that promotes healthy root growth. Consider this astounding fact: One teaspoon of healthy soil contains more microorganisms than there are people on Earth.

Comparison of worm castings with average soil

Comparison of worm castings with average soil

Once the worms have had time to work their magic, you can harvest the castings from your compost bin or pile by a simple method that Anderson calls “worm wrangling.” You simply dump the compost on a tarp and the worms move to the bottom of the pile to escape the sunlight. You collect the castings by scooping up the top layers of the compost and allow the worms to move downward. You can then return the bottom level of the compost with the worms back to the pile.

My compost pile is not half as organized or efficient as Anderson’s system, but I can attest that the worms have been essential to converting my Colorado clay into fertile soil. My red-wigglers have continued to multiply in the pile, while happily converting leaves, kitchen waste, chicken manure, rabbit manure, and plant trimmings into black gold, which I spread around the garden. My chickens help turn over the compost pile and consume some of the worms, but in return I get healthy, fresh eggs. After learning from the Worm Man, I now have a much stronger appreciation for the robustness of a complex and well-diversified natural food web, as well as a deeper understanding that we all ultimately come out of the soil, and depend on healthy soil to sustain us. As John Anderson would say, “visualize global worming.”

Images by Boulder Vermicomposting, John Anderson, and Peter van Gorder

Earth Day is tomorrow. Please try starving a landfill and feeding a worm.