The Ronettes, early 1960s

When I initially contemplated this series, I began with the intention of exploring areas of the music world I felt merited reexamination. Occasionally, this means that I choose to focus on genres and artists that have been overlooked in their significance (Twee Pop, Black Flag, New Jersey’s musical legacy) and other times, this means that I try and advocate on behalf of artists I feel have been unjustly maligned or inaccurately judged, as I did with the Grateful Dead. Rarely, and most difficultly, those two strains intersect to create a genre/artist that feels both critically under-appreciated and unfairly appraised as insignificant fluff. Such is the case with the Girl Groups of the 1950s and 1960s.

Girl Groups essentially rose to prominence in the halcyon days of rock’n’roll and sat at the nexus of generational, racial and sexual lines. Oddly, this rather unique position probably enabled history’s chroniclers to overlook these artists, rather than appreciate the role they played in the development of pop music. In this piece, I will try to address a number of these topics, specifically as they relate to this particular genre but please note that these social issues–of class, of gender, of race–are extremely complex and at no point do I intend to present myself as an expert on these matters.

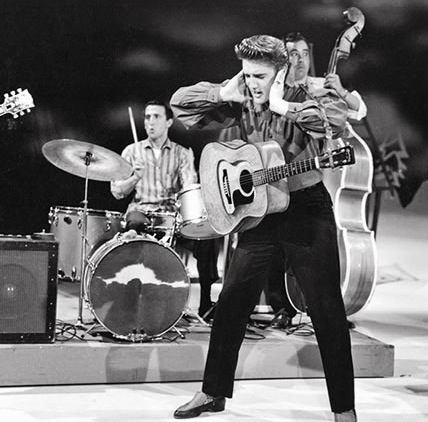

If I were to ask you to give me a brief history of rock and pop music, you would probably relay the same handful of events: In 1956, Elvis gyrated his hips during a television appearance and scandalized the nation. Over night, the telegenic singer transitioned from the moderately-successful Sun Records artist to RCA Nashville’s megastar. Rock and roll as we know it was born. In 1964, the Beatles “invaded” America, played the Ed Sullivan show and everything was forever changed. The artistic zenith of the Baby Boomer generation came five short years later when 400,000 of them coincided peacefully at a three day performance.1 Disco came on the heels of the twilight of the age of Aquarius and was followed by the advent of punk in the second half of the 1970s. In the 1980s, television took a gamble on an upstart called MTV and hip hop began its ascent to the American mainstream. In 1991, “punk broke” and Nirvana killed off the mascara-caked Sunset Strip bands. Subsequently, we descended into a vacuum of nothingness.

Well, that’s the way the story goes for many music journalists and it is about half right. The problem with this narrative is that it paints a narrow, linear progression that can only come from hindsight and at the expense of accuracy. The evolution of popular music is knotty; it is full of diversions, retreads, dead-ends, manipulations and some completely illogical left-turns. It is not hard to see why the above-mentioned version of events is appealing with its easy cause/effect logic but it also neglects legions of massively important music–without which, it would be inconceivable to imagine all the music we have today–while (possibly) over-stating the accomplishments of a few artists.

The Andrews Sisters

The Andrews Sisters

Running parallel to the accuracy concern are the matters of perspective. That is, music journalism tends to be dominated by a particular demographic: white, middle-aged men. To some degree, our relationship with art is shaped by our backgrounds and individual histories. We like things that consciously or subconsciously remind us of ourselves, so it stands to reason that white men would mostly write about the achievements of other white men. Add to that centuries of institutionalized sexism and racism and it becomes increasingly apparent that history’s victors write the narrative.

Prior to the Great Depression, female vocal groups were scarce with one notable exception: a trio of sisters called the Boswell sisters (a jazz vocal group popular in the late 1920s and 1930s). In 1937, three sisters named LaVerne, Maxene, and Patty Andrews began working their way around the vaudeville circuit as a trio modeled after the Boswell Sisters. Like their antecedents, the Andrews Sisters specialized in complex vocal harmonies. Though the sisters were white, their music drew heavily from the era’s black music, such as rhythm and blues, bebop, jump blues and jazz and their interpretation of these genres proved highly popular. USO tours and patriotic film appearances made the sisters household names and synonymous with World War II-era optimism. To this day, the Andrews Sisters remain the most successful girl group of all time and have sold over seventy-five million albums.

The economic boom that followed America’s involvement in World War II had a profound effect on popular culture in ways that few could have anticipated. Blooming prosperity meant that for the first time, many American teenagers were staying in school and putting off work. This in turn meant that they had time and pocket money to spend on leisure activities and thus, buying power. Hollywood and the music industry quickly realized that there was an entire untapped market for material geared toward teenage girls and that their potential for profit was enormous. Teen dreamboats like Ricky Nelson and Frankie Avalon cornered one aspect of the teen market and female vocalists such as Lesley Gore cornered the other.

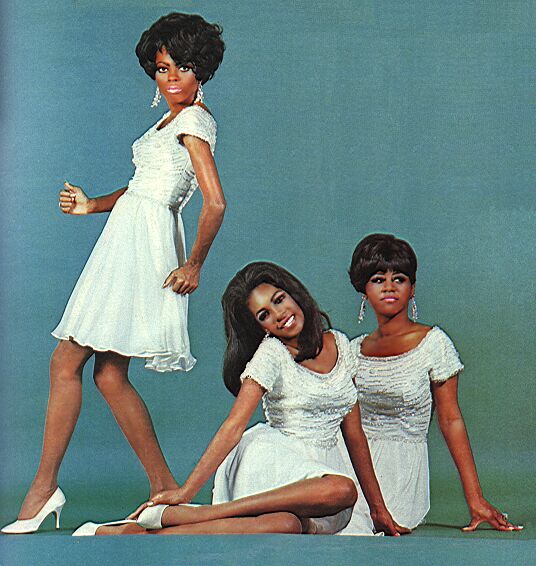

The Supremes looking gorgeous

The Supremes looking gorgeous

Around the same time, black music in the form of Rhythm and Blues was emerging as a popular force. Black and white musicians had long married and borrowed influences from one another (usually with white musicians taking credit) but artists like Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and Bill Haley gained popularity by brazenly playing “black music” and harnessed the ensuing controversy to their advantage.2 America’s teenagers had a ravenous appetite for this new music and unlike many of their parents, they did not care that the music was associated with African American culture. Girl groups–or musical acts consisting of female vocalists (not to be confused with all-girl bands)–hit all the sweet notes with the emergent teen culture. Girls groups (generally) consisted of telegenic young black women in their late teens or early twenties whose soaring, majestic vocal melodies were amplified by muscular orchestration. The songs told stories of broken hearts, yearning and teenage love. They were the perfect soundtrack for malt shops, car rides and singing into a hairbrush in your childhood bedroom.

The Shirelle’s 1961 #1 hit “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” is generally cited as the song that kicked off the girl group craze.3 The song, like many of its era, was written by one of the the Brill Building’s songwriting teams (in this case, the song was written by the husband and wife songwriting team Carole King and Gerry Goffin).4 As with many contemporary pop acts, the girl groups of the 1950s and ’60s did not write their own material. Professional songwriters, such as Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller5, Goffin and King, Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, Ellie Greenwich, and Phil Spector wrote lyrics and composed songs (often handling production duties, as well) and then offered them to artists with whom they had a contractual relationship.

The most classic singles of the girl group era were produced by Phil Spector at Gold Star Studios in Los Angeles. Spector has become notorious for his violent personal life and his eccentric behavior but prior to becoming a tabloid fixture, he was known as one of popular music’s true creative geniuses.

Spector and the Ronettes at Gold Star, early 1960s

Spector and the Ronettes at Gold Star, early 1960s

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, the overwhelming majority of music was heard on AM radio, which was broadcast in mono (rather than stereo) sound. Mono–or monaural–sound is when one microphone, one loudspeaker, or sometimes multiple microphones are fed through a single channel. Since the mid-1960s, mono has become decreasingly common; stereophonic sound (or sound configurations consisting of two or more channels) provides listeners with the perception of auditory perspective and is standard on FM radio and contemporary sound entertainment. The compressed sound of mono recordings suited the mediums of the era (again, AM radio and poorly-constructed turntables) but it produced music that sounded flat and distant to the listener. To remedy this problem, Phil Spector devised a recording process dubbed “the Wall of Sound.”

Gold Star Studios was Spector’s preferred recording destination because it featured echo chambers which were commonly used for classical recordings. To create the Wall of Sound effect, Spector would set up microphones in the studio, which transmitted sound to the subterranean echo chambers, which were also appointed with methodically placed microphones and speakers. The sound transmitted to the echo chambers would reverberate and then be captured by the chamber’s microphones and fed back to Spector’s control room and recorded. The vocal performances were supported by an uncommonly large amount of instrumentation–for pop music, at least. The songwriter Jeff Barry recalled that it was not uncommon for Spector to have five guitars, two basses, strings, percussion, tambourines, maracas, bells and seven horn players performing on one pop song. The results were absolutely spectacular, but it could also be described as textbook “overkill.” In any event, the recording technique made Spector’s girl groups shine on the radio.

Arguably, the best example of the Wall of Sound production style is on the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby.”

- I am continually, genuinely surprised by the ever-growing mythology surrounding Woodstock. The performances were largely forgettable, if not downright middling and surely, a three-day festival could never be the artistic high point of a decade that included Pet Sounds, Slaughterhouse-Five, In Cold Blood, Rosemary’s Baby, Bonnie & Clyde, Pop Art, Minimalism, Richard Serra and countless other creative achievements. Besides, Monterey Pop was the superior festival. Everyone knows this.

- You know how you always see Little Richard on television, glitter shimmering on his lapels, ranting and raving about how his work was stolen from him by the likes of the Beatles, Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, the Stones and well, pretty much everyone? He is usually brushed off as a delusional lunatic but the truth is that he is not wrong. Seriously, listen to the first 20 seconds of “Keep a Knockin'” and then listen to the opening of Led Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll.” Sound familiar? It should. (This should probably be another article.)

- The Shirelles’ hit was the first girl group number one hit but it was not the genre’s first top 40 hit. The Teen Queens became one-hit wonders over night with “Eddie My Love” in 1956 and then the Chantels scored a hit with 1958’s “Maybe.” Carole King sang her own version of “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” on her solo album Tapestry released in 1971.

- The Brill Building is located at 1619 Broadway in New York City. At the peak of its influence, the building housed eleven floors of studios, songwriters, composers and music publishers. The Glenn Miller Orchestra, Bennie Goodman Orchestra, Paul Simon, Carole King & Gerry Goffin, Neil Diamond, Burt Bacharach, Laura Nyro, Phil Spector, Ben E. King and Don Kirshner were among the luminaries who called the Brill Building home. In the 1950s and 1960s, the building was known for producing a particular kind of pop song, which became known as the “Brill Building Sound.” This pop style was heavily influenced by Latin music, R&B and was perfectly calibrated for heavy radio play.

- Leiber and Stoller were also members of the Brill Building crew and their credits include Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me,” “Hound Dog” and “Jailhouse Rock.” There are too many well-known songs that were written by the above-mentioned songwriters, but if you take a quick peak at the pop charts from the early 1960s, many of the songs will be products of the Brill Building’s inhabitants.

Coming up in Part 2: The decline of the girl groups, their legacy and what it says about gender, race and perspective in music.

[Full post republished and previous “Crate Digging” installments from gracefultongue.com]

The Andrews Sisters

The Andrews Sisters The Supremes looking gorgeous

The Supremes looking gorgeous Spector and the Ronettes at Gold Star, early 1960s

Spector and the Ronettes at Gold Star, early 1960s