Nearly five months after a magnitude 9 earthquake unleashed a massive tsunami, caused northeastern Japan to spring 13 feet to the east and utterly crippled the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, details about the extent of the damage and the amount of radiation that’s still spewing from the troubled reactors is only now coming to light. The Japanese government, in collusion with the nuclear regulatory agency and Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) tried to hide critical information from the public concerning radiation levels in the Tohoku region not only to ostensibly curb panic, but to avoid having to pay damages to those who make their living in the region and/or shoulder the expense of relocating even more evacuees.

Since March 11, the government (and the domestic and foreign press, for the most part) stated that the tsunami (which was estimated to be 45 feet high when it crashed into the plant) knocked out the electric power generators (stored in the basement… good job guys) which resulted in the emergency cooling functions to break down, which lead to the current meltdown. But the data shows that the quake itself – not the tsunami – caused the nuclear crisis.

In fault-line riddled Japan, there are 54 nuclear power plants, of which 35 are currently offline, either due to routine maintenance or because of popular backlash and concerns over seismic activity. If it’s true that the 3/11 earthquake was the major factor that led to the meltdown, it would mean that all the reactors in Japan are at the same risk. In this article, David McNeill and Jake Adelstein dig through TEPCO’s shady history of covering up safety problems at the aging plant and how a whistleblower’s warnings were buried.

Problems with the fractured, deteriorating, poorly repaired pipes and the cooling system had been pointed out for years. In 2002, whistleblower allegations that TEPCO had deliberately falsified safety records came to light and the company was forced to shut down all of its reactors and inspect them, including the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant. Sugaoka Kei, a General Electric on-site inspector first notified Japan’s nuclear watchdog, Nuclear Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) in June of 2000. The government of Japan took two years to address the problem, then colluded in covering it up — and gave the name of the whistleblower to TEPCO.

The pipes are necessary to provide coolant to the reactor and siphon off excess heat. If the pipes fractured and burst after the quake (as it appears likely), the meltdown began well before the tsunami hit. The authors spoke with current and former nuclear power plant workers (who were granted anonymity, which, given TEPCO’s alleged ties to the mafia, is probably a good idea). The information gleaned paints a grim picture:

Worker A, a 27-year-old maintenance engineer who was at the Fukushima complex on March 11, recalls hissing, leaking pipes. “I personally saw pipes that had come apart and I assume that there were many more that had been broken throughout the plant. There’s no doubt that the earthquake did a lot of damage inside the plant. There were definitely leaking pipes, but we don’t know which pipes – that has to be investigated. I also saw that part of the wall of the turbine building for reactor one had come away. That crack might have affected the reactor.”

(…)

Worker C was coming into work late when the earthquake hit. “I was in a building nearby when the earthquake shook. After the second shockwave hit, I heard a loud explosion. I looked out the window and I could see white smoke coming from reactor one. I thought to myself, ‘this is the end.’”

When the worker got to the office five to fifteen minutes later the supervisor immediately ordered everyone to evacuate, explaining, “there’s been an explosion of some gas tanks in reactor one, probably the oxygen tanks. In addition to this there has been some structural damage, pipes have burst, meltdown is possible. Please take shelter immediately.”

(…)

Tanaka Mitsuhiko, a former nuclear power plant designer and science writer asserts that at least the Number One reactor melted down as a result of the earthquake damage. He describes it as a loss of coolant accident (LOCA). “The data that TEPCO has made public shows a huge loss of coolant within the first few hours of the earthquake. It can’t be accounted for by the loss of electrical power. There was already so much damage to the cooling system that a meltdown was inevitable long before the tsunami arrived.”

(…)

On May 15, TEPCO went some way toward admitting at least some of these claims in a report called “Reactor Core Status of Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station Unit One.” The report said there was pre-tsunami damage to key facilities including pipes. “This means that assurances from the industry in Japan and overseas that the reactors were robust is now blown apart,” said Shaun Burnie, an independent nuclear waste consultant. “It raises fundamental questions on all reactors in high seismic risk areas.”

After several failed attempts, the workers at the plant are gradually bringing the reactors under control. TEPCO aims to have “cold shutdown” at the plant by early next year. Yet there are still massive amounts of radioactive particles both in the plant (an exhaust duct between the number 1 and 2 reactors showed 10 sieverts per hour of radiation, enough to kill a person exposed for mere minutes. The monitoring equipment’s highest reading is 10 sieverts, meaning the actual amount of radiation is possibly even higher.)

Other nuclear plants in Japan will be subjected to stress tests in order to prove their ability to withstand earthquakes and tsunamis.

The lack of publicly available information about radiation in the early days of the crisis led to citizens buying dosimeters and testing their neighborhoods themselves. Some dosimeters are more reliable than others, and readings can vary depending on a variety of factors, but the move amounts to a vote of no confidence in the Japanese government and a gagged, docile media.

And it turns out their fears are well founded. In this recent article from the excellent Hiroko Tabuchi at the New York Times, information about the true volume and extent of radiation contamination was supressed by the government:

In interviews and public statements, some current and former government officials have admitted that Japanese authorities engaged in a pattern of withholding damaging information and denying facts of the nuclear disaster – in order, some of them said, to limit the size of costly and disruptive evacuations in land-scarce Japan and to avoid public questioning of the politically powerful nuclear industry.

A computer system that forecasts the amount and dispersal of radiation, System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information, or Speedi, had been producing maps and data about the radiation plumes from the reactor. But because sensors at the plant itself had been knocked out, the data was considered “incomplete” by the authorities, and was not immediately released to the public.

But even with incomplete data, Mr. Kosako said he urged the government to use Speedi by making educated guesses as to the levels of radiation release, which would have still yielded usable maps to guide evacuation plans. In fact, the ministry had done precisely that, running simulations on Speedi’s computers of radiation releases. Some of the maps clearly showed a plume of nuclear contamination extending to the northwest of the plant, beyond the areas that were initially evacuated.

(…)

A wider evacuation zone would have meant uprooting hundreds of thousands of people and finding places for them to live in an already crowded country. Particularly in the early days after the earthquake, roads were blocked and trains were not running. These considerations made the government desperate to limit evacuations beyond the 80,000 people already moved from areas around the plant, as well as to avoid compensation payments to still more evacuees, according to current and former officials interviewed.

(…)

Mr. Kosako said the top advisers to the prime minister repeatedly ignored his frantic requests to make the Speedi maps public, and he resigned in April over fears that children were being exposed to dangerous radiation levels.

The unwillingness of the government to release data to the public, ostensibly for fear of causing panic and confusion, smacks of a distrust of the populace to make decisions on their own and a concerted effort to continue the infantilization of the general public and to reinforce the perception that Government and Big Business Know Best.

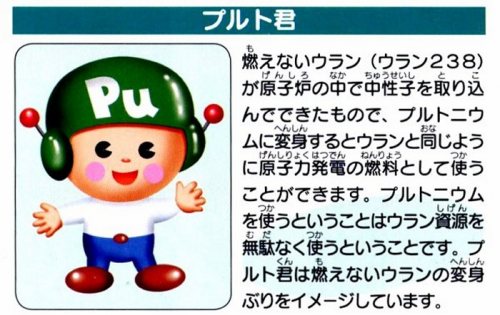

TEPCO has a couple of mascots (cute characters used by companies and official agencies to create a warm, fuzzy, likeable brand – heck, even the logo for TEPCO bears a striking resemblance to Mickey Mouse’s silhouette), the most ironic being Plutonium-kun (Little Plutonium). From Spike Japan:

I once wrote of Yu-chan, the cartoon mascot of the battered former coal town of Yubari, that “Japan of course has a massive talent for cuteification: if you can cuteify coalmining, you can cuteify anything”, but never in my darkest nightmares did I dream of encountering Plutonium kun. He’s a hard lad to track down, not having proven as popular as Denko chan, but I did manage to salvage this image from the recesses of the Internet.

The text, with its furigana reading aids above every kanji character and its childish vocabulary, in which “non-fissile uranium” is referred to as “unburnable uranium”, is aimed at the very young, to get them hooked on plutonium from an early age, and demands, nay begs, to be translated, so here goes:

“Plutonium is made by having unburnable uranium (uranium 238) soak up neutrons in a nuclear reactor, and when it turns into plutonium it can be used as a fuel in nuclear power generation, just like uranium. By using plutonium, uranium resources can be used more economically. Plutonium kun is a visualization of unburnable uranium being transformed into plutonium.”

Plutonium-kun was even featured in an anime, where he gets a friend to drink a glass of liquid plutonium, claiming brightly that “I’m hardly absorbed by your stomach or intestines and I’m expelled by your body, so in fact I can’t kill people at all.”

(The anime can be viewed here. The scene in question is here.)

If only it were true. Radioactive contamination has already entered the food supply, most notably in the case of thousands of cattle fed cesium-contaminated hay. Some of the affected beef made it to market in dozens of prefectures and in some cases was sold before the government recalled it. Farmers protesting TEPCO brought a cow to their Tokyo headquarters. Worries over contaminated rice led to an accidentally aired joke about “Mr. Cesium” on Fuji TV, but recently tested rice in Chiba prefecture shows no radiation.

Tepco posted a loss of $15.2 billion. The president, Masataka Shimizu resigned, with a golden parachute worth $6.5 million and was granted a consulting contract with the company to the tune of $1.2 million per year. Tepco – redefining “failing upwards.”

*

So, what now? What to do? Aside from donating to charities to help survivors of the triple disaster, there are several worthy volunteer groups who are doing what they can to provide needed supplies and information to Japanese citizens.

Safecast.org was founded to provide real-time radiation data from 500,000 points across Japan. The team has several volunteers driving across the country, posting readings from some areas where no government information is available.

Second Harvest has been delivering donated food supplies to displaced Tohoku residents since the early days of the crisis.

Bikes for Japan is supplying bikes donated or collected from abandoned lots to people in the Tohoku region, where roads are still damaged and impassable by car.

Japan Earthquake Animal Rescue and Support (JEARS) has been rescuing animals (often pets) left behind in the rubble of the tsunami or within the evacuation zone around Fukushima. One of the volunteers blogs here.

Top pic via