In mid-December D.T. Max, author of the first full-length biography of the American novelist David Foster Wallace — titled Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story — made a special appearance at Harvard University. Max was scheduled to participate in a “public conversation” with literary critic and part-time Harvard Professor James Wood.

The venue was Emerson Hall, one of Harvard’s humanities buildings. Emerson contains a large lecture hall, seating about 250 people. And on this evening — during the university’s presumably intense final-exam period — the room was still three-quarters full.

This public appearance by biographer Max was framed a bit oddly. It wasn’t promoted as a book signing, exactly (although it turned out after the “conversation” ended that books were signed at a makeshift table in the hallway outside). And this curious promotional event didn’t seem to fit easily into a regular book tour. Max’s book had come out at the end of August, and he’d already done a Boston-area reading and signing for it in late October.

And the actual start to the event was even odder yet. Apparently it’s a well-known irony at Harvard that the university frequently celebrates writers and other alumni who were actually quite miserable during their time in Cambridge. And as we were forthrightly reminded in the evening’s introductory remarks, few people could have been more miserable at Harvard than David Foster Wallace. Wallace enrolled in the university’s (phenomenally small and selective) graduate philosophy program in 1989 — but after about three weeks he reported suicidal ideation, had himself hospitalized, and then began the long task of getting clean of his substance addictions. If you’d rather go to rehab than to class, then I’d say you’re pretty miserable.

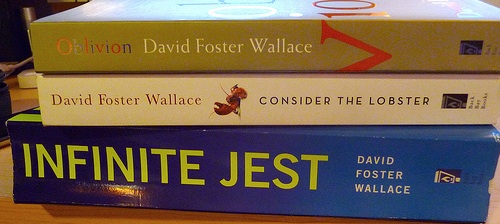

Next up on this evening, a couple of undergraduates read nifty passages from Wallace’s work — one from an early section of the novel Infinite Jest, and one from the title essay in the collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments

. However, this segment was somewhat clumsily introduced: An academic from the sponsoring humanities center described it as a way to pursue the evening’s agenda while Wallace’s prose was still “hanging in the air.” This was a pretty unfortunate choice of words for celebrating David Foster Wallace, who committed suicide by hanging in September 2008. But if there’s one recently deceased American writer who could be said to be immune to unfortunate ironies (because he forswore them so earnestly himself), then it’s probably Wallace.

And then it was time for Max to take questions, both from Prof. Wood and from the audience. In the early going, a number of worthy topics were introduced: Wallace’s relationship to literary “realism”; the role of faith in his work and life; mother figures; and the theme of boredom, as it emerged in his later books (and especially the unfinished, posthumously published The Pale King).

But after a few attempts to discuss those high-minded subjects — and after the panel started taking questions from the floor — the evening turned toward what everyone was surely there for: Speculations on why Wallace killed himself. As Wallace’s biographer (and the only one, for right now), Max had already indulged in some minor speculations in print while constructing a narrative of the writer’s life. But this audience was hungry for more.

And Max obliged them as well as he could: He’s an affable guy who wants to cultivate a readership. (Max is also a trifle long-winded in person — although he’s absolutely terse when compared with James Wood, who can hardly utter a complete prepositional phrase without interrupting it twice with “ums” and “uhs.”) So in this unique environment, Max gamely offered whatever views he could muster on the topics that people just couldn’t help asking about.

And most of what people wanted to know — even four-plus years after Wallace’s suicide — was: Why did he do it? Why did David Foster Wallace intentionally terminate one of the most storied careers in contemporary American literature? It’s a massive stumbling-block of a question — one that can never be answered to anyone’s real satisfaction.

Relying on his research into the man’s life, Max tried his best to address this question anyway, modestly and honorably. He attempted to parse out the basic types of depression that Wallace might have suffered from — existential, emotional, chemical, other. He offered his observation — not widely known — that Wallace’s effort to change his anti-anxiety/anti-depressant medication in 2007 (which many believe precipitated the depressive spiral that he failed to survive) was not unprecedented in his life…yet in the past he’d always managed to re-stabilize himself afterward.

And Max even took the ultimate step, offering a kind of unified-field theory of Wallace’s demise: Based on what he read in Wallace’s drafts and correspondence, Max thought it was possible that Wallace took his life because he was having too much trouble writing. (Which problem he might have been trying to address by changing his medication.) And the reason Wallace was having trouble writing — Max further speculated — was because he had taken up writing challenges which were just too damned hard. Perhaps with The Pale King (and perhaps also with Oblivion, Wallace’s amazingly intricate final collection of short stories), Wallace had chosen subjects which were simply too difficult to write about — including boredom and depression. Maybe those subjects are too difficult for anyone to write about.

I imagine that for most contemporary authors, a critical consensus about their work (and life) begins to emerge a few years after their passing. This consensus isn’t permanent, or perhaps even correct. But in Wallace’s case, I think his most dedicated audience — or at least the one that’s able to show up at a Harvard lecture hall during exam week — hasn’t yet reached that point. This audience is still going through another, antecedent process, which you might think of as the stages of literary grief. I can’t think of any better way to describe this unusual, dolorous little public event held on a wintry Monday night in a Harvard classroom. This audience still misses Wallace, still can’t believe he’s gone, and still grieves — in the oddly dry-eyed and public way that people sometimes do, about writers anyway.

Photo by user Benjamin A. Stockwell via Flickr.