If you have ever wandered past a skate park, rock club or a seedy neighborhood in your town, chances are that you have seen Black Flag’s stark, iconic logo scrawled on the surface of a wall, skate deck or t-shirt. If you are older (or just like hanging out with old punks), you have probably encountered a number of poorly-done tattoo replicas of the band’s Ray Pettibon-designed logo on sagging biceps. The band, like the logo, has become an indispensable insignia of punk anti-authoritarianism and underground culture for marginalized kids everywhere. A quarter century since they disbanded, Black Flag continues to have a strong influence on the worlds of punk, indie, and metal music.

Over the course of their decade-long career, Black Flag managed to exemplify a number of superlatives–both good and bad. They were loud, hard-living, hard-playing, violent, funny, sexist, sexy and best of all, they scared the shit out of concerned parents, police departments and low-level bureaucrats everywhere. What more could an angsty teen want from a band?

Black Flag was founded in 1976 by guitarist Greg Ginn and was among the handful of groups responsible for creating Los Angeles’ nascent hardcore scene. By the late ’70s, music’s taste-makers were moving away from the sound that marked punk’s first wave. All the cool kids, so to speak, were into the arty post-punk that was emerging from the UK with groups like Wire and Joy Division. However, any kid who grew up in the suburbs can testify to the delay that exists between the time urban hipsters create art and time it finally reaches the rest of the country. In the pre-internet/pre-MTV days, this temporal gulf was even wider. Just as the artistic community and urban music nerds were leaving the Ramones, the Sex Pistols and the Dead Boys behind, suburban kids in Southern California were just starting to pick them up. Excited by having access to this music, those same suburban kids began to create their particular riff on punk and referred to it as “hardcore.”

Hardcore was distinct from first-generation punk in ways both musical and aesthetic. Unlike their predecessors, hardcore kids were not arty street urchins. Many of them sported shaved heads, muscular physiques (courtesy of their surf and skate-centric lifestyle) and the suburban uniform of t-shirts and skate shoes. This was a far cry from Richard Hell’s artfully disheveled style, David Johansen’s drag or Sid and Nancy’s black leather and dog collars. Further contributing to this disparity were the respective scenes’ substances of choice. Punks in New York had a known affection for speed and heroin while the kids partaking in the hardcore scene rarely touched more than alcohol.1

Musically, hardcore was faster, heavier, louder and more aggressive than punk’s previous incarnation. Instead of focusing on melody, it tended to place a greater emphasis on rhythm. (See: “Rise Above” the lead song off of Black Flag’s Damaged. The drums and bass drive the song and provide it with a sense of urgency.) The music was more structurally loose than most punk as well. As rock critic Steve Blush noted in an article for Uncut, “The Sex Pistols were still rock’n’roll…like the craziest version of Chuck Berry. Hardcore was a radical departure from that. It wasn’t verse-chorus rock. It dispelled any notion of what songwriting is supposed to be. It’s its own form.” Realistically, this dramatic turn in style was more of an accident than deliberate departure. Few members of hardcore bands were classically-trained musicians and even fewer were privy to punk culture’s inner circle, and thus, they were not beholden to its sanctified rules. They were unafraid of indulging their desire to play guitar solos, experiment with feedback or screw around with tempo and embraced the possibilities presented to them by DIY culture.

Greg Ginn was raised in Hermosa Beach, California in a middle class home. His father was a college professor and as a child, Greg was quiet and solitary. At age twelve, he started his own newsletter and SST (Solid State Transmitters)–a business that sold modified surplus World War II radio parts through mail order. Ginn was, in other words, a bit of a nerd. Unlike most children of the ’60s, Ginn did not grow up as a rock’n’roll fan. He believed the music was elemental and stupid, so he preferred the instrumental complexity of jazz and the message-laden music of folk singers. There was, however, one exception to his dislike of rock–The Grateful Dead2, which he would state was his favorite band of all time.

![]()

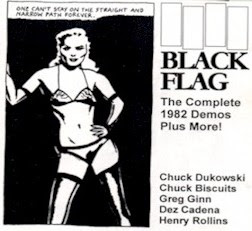

Ginn’s opinion of rock changed when he came across a copy of Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel” single. He began playing guitar and eventually met Keith Morris–a classmate and affable, hard-partying loudmouth with a taste for hard rock, elephant tranquilizers, and cocaine. Together with Greg’s brother, Raymond, the trio began practicing under the name Panic. The group eventually changed their name in 1978 (to avoid confusion with another L.A.-area band using the name) to Black Flag3. Morris initially had his sights set on being the band’s drummer but Greg felt that Morris was a natural frontman and pressured Keith to assume the responsibility of lead vocals.

From the band’s inception, the one quality that would forever distinguish them among their contemporaries was their tireless, militaristic work ethic. At Greg’s insistence, the band regularly practiced eight hours a day, six days a week. Their practice schedule made finding additional band members exceedingly difficult, so very often, Greg and Keith would practice alone or with Ray sitting in. The initial absence of a bass player had a marked effect on Greg’s guitar work; his guitar was tuned down and had a heaviness to it that sounded unlike other guitarists at the time. With new bassist Chuck Dukowski and Brian Migdol on drums, the group recorded their first EP, Nervous Breakdown.

Nervous Breakdown is Black Flag at their most conventionally punk. Keith Morris’ vocals bear a striking resemblance to those of the Sex Pistols’ Johnny Rotten; they are snotty, adolescent and downright bratty. The production on the EP is low-budget and sleazy and with four songs, the record clocks in at five and half minutes. Keith Morris left the group shortly after the record’s completion citing conflicts with Ginn and his own “freaking out on speed and cocaine” as the reason. He would go on to form L.A. hardcore band the Circle Jerks shortly thereafter. For some, this recording would be considered Black Flag’s finest moment and while that assertion lends itself to considerable debate, it is irrefutably the album that gave Black Flag credibility among L.A.’s punk community.

With Keith out of the band, Black Flag was in need of a new singer and they found that person in Ron Reyes4. Reyes’ tenure in Black Flag was short-lived and he quit the band in the middle of a gig, forcing them to play “Louie, Louie” repeatedly for over an hour. At the time, Reyes was drinking heavily and had grown weary of the constant violence associated with Black Flag shows. Fans, eager to blow off steam and emboldened by too much alcohol, used the band’s gigs as a venue for fighting. Slam-dancing escalated into full-on brawls, which in turn became riots. The Los Angeles Police Department caught wind of the band’s reputation and began harassing the members. SST’s phone lines were tapped and the police would send cops in riot gear to shows, where they would get into fights with fans. Batons cracked skulls, a cop car was set on fire and soon, venues were refusing to book the band, regardless of how popular they had become.

The group’s next singer was Dez Cadena, a friend and the son of a well-regarded A&R man in the jazz world. Cadena was a good fit for the band but his inexperience as a singer took a toll on his voice. It was decided that Cadena should switch to rhythm guitar and once again, the band was missing a singer. Enter: Henry Rollins.

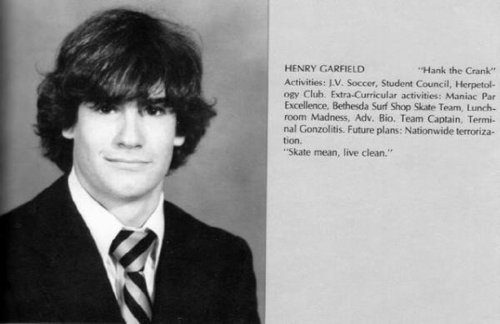

Henry Garfield grew up in Glover Park, Washington, D.C. His parents divorced when he was a toddler and despite being of relative affluence, Garfield’s childhood was hardly idyllic. His father, an economist, was a racist misogynist who mentally abused Henry until he finally severed ties with him. In a 1994 interview with Rolling Stone, Henry spoke of being molested by his mother’s boyfriend and being alienated and reclusive as a child. He suffered from ADHD and was given Ritalin, which reduced him to a zombie who sat in class and ground his teeth compulsively. By the time he reached his teen years, Henry had accumulated a great deal of rage, which led to lousy grades, bad conduct, and expulsion from two schools. At her wits’ end, his mother sent Henry to Bullis School–a notorious military academy–where he would learn discipline and develop an interest in weight training.

Henry and his childhood friend, Ian MacKaye were fans of Black Flag, which had gathered an East Coast following thanks to their extensive touring and notoriety. When the band played a gig in New York, Henry requested that the band play their song “Clocked In” and jumped on stage to sing it with them. The band was impressed with Henry’s natural stage presence and invited him to audition for the position of lead singer. He accepted and the band offered him the job. Dez finished the tour as the group’s singer and Henry lugged equipment while he learned Black Flag’s songs.

Touring with Black Flag opened Henry’s eyes to the violence of the hardcore scene. In one city, a bouncer harassed a female audience member while Black Flag was performing. Incensed, Dukowski used his bass to brain the bouncer, who fought back. An audience-wide brawl ensued and the band barely escaped.

The group returned to Los Angeles and recorded their first full-length album, Damaged. The album consisted of a number of songs the group had written while Morris and Reyes were members and a few tracks had been recorded previously as B-sides and singles. For many listeners–myself, included–Damaged is the definitive product of the hardcore movement. The album opens with the feral aggression of “Rise Above,” a blood-boiling call-to-arms, and the unflagging energy permeates the ensuing fourteen tracks. Former singer, Keith Morris, is referenced in the satirical “Six Pack” (which features the greatest mounting tension/release dynamic ever committed to tape) and the off-key dude chorus of “TV Party” provides the album with a dose of much-needed levity. If there is one criticism to be made, it is that the production of the album lacks the intensity the material necessitates. Spot, SST’s resident producer, had a talent to making everything he touched sound thin and labored.

The band embarked on a grueling tour to support the album. Henry–who was now using the surname “Rollins”–added a new machismo to Black Flag. The gawky Ginn and schlubby Dukowski may have shaped the sound of hardcore, but Rollins, with his youth, shaved head, muscular build and tattoos, became the movement’s poster boy–a role he was eager to play. Clad only in black gym shorts, Rollins would pace the stage like a caged animal while the band warmed up. As they tore through song after song, Rollins’ bellicose military bark spit out lyrics in a manner that highlighted both his self-loathing and narcissism. Ginn may have written the words to many of those songs but Rollins lived them.

Audience members assumed Rollins’ combative, alpha male stage persona translated into a desire for physical confrontation. Sometimes this assessment was correct and other times, the ceaseless provocation wore on Rollins psychologically. While he sang, audience members would spit (“gobbing” in UK punk parlance), punch, stab, burn with cigarettes and otherwise antagonize Rollins until he snapped and fought back. After the sets were complete, Rollins’ bloodied chest served as a summary of the nights’ interactions with the audience.

After touring continuously for three years, Black Flag returned to the studio to record their second full-length album, My War. This album proved controversial among the hardcore crowd because it marked the first time that punk overtly moved in a metallic direction. Musically, the band was growing beyond the confines of punk and sought inspiration from free jazz and big band music, as well as metal godfathers such as Black Sabbath. Much to the irritation of their fans, the guys of Black Flag began growing out their hair5 and experimenting with sludgy, doom-laden songs which were substantially slower then the band’s previous work. Some punks may have hated the album but it became a touchstone for future grunge and metal bands.

The tour behind the album was probably Black Flag’s peak as a live act. They were tight, professional and disciplined. Dukowski had stepped down as the group’s bassist and was replaced by Kira Roessler. Roessler was an objectively better bassist than Dukowski had been and her position as the sole female member of hardcore’s biggest band made her a hero among punk girls6. The tour was arduous and tensions began mounting within the band. Rollins began retracting from his fellow band members, eating alone and riding in the back of the equipment van alone in the dark. He and Ginn, in particular, began to dislike one another. Initially, Ginn had appreciated Rollins’ eagerness to grant interviews or pose for photos but eventually, he resented how his band had become inseparable from its singer. Further, Ginn would suggest that Rollins had become increasingly humorless and ever-more self-pitying.

The tour behind the album was probably Black Flag’s peak as a live act. They were tight, professional and disciplined. Dukowski had stepped down as the group’s bassist and was replaced by Kira Roessler. Roessler was an objectively better bassist than Dukowski had been and her position as the sole female member of hardcore’s biggest band made her a hero among punk girls6. The tour was arduous and tensions began mounting within the band. Rollins began retracting from his fellow band members, eating alone and riding in the back of the equipment van alone in the dark. He and Ginn, in particular, began to dislike one another. Initially, Ginn had appreciated Rollins’ eagerness to grant interviews or pose for photos but eventually, he resented how his band had become inseparable from its singer. Further, Ginn would suggest that Rollins had become increasingly humorless and ever-more self-pitying.

The band subsequently recorded Family Man, Slip It In, Loose Nut and In My Head. Slip It In and Loose Nut both exhibited a disturbing–for its apparent lack of irony–vision of male virility. The title track of Slip It In, for example, conveys deeply misogynist views of women and female sexuality but more to the point, the subsequent albums were ever more over-wrought and lacking in perspective. Always the passive-aggressive type, Ginn displayed his resentment of Rollins by burying his vocals in the mix. Rollins, in response, would change lyrics to mock Ginn when they played live and vocally disapproved of Ginn’s prodigious marijuana habit. Further, the guys tried to harangue the tomboyish Roessler into dressing more provocatively, which she understandably resented. Things were falling apart and in 1986, Ginn pulled the plug on Black Flag.

Black Flag remains an important milestone in the history of popular music. For a decade, they embarked on grueling, interminable tours that brought punk music to regions of the country that major record labels ignored. With Ray Pettibon as the creative force behind their posters and album covers, the band created an aesthetic that would be much imitated by subsequent generations of punk bands. Moreover, with SST’s roster of talent, the label managed to dictate the direction of indie music for much of the ’80s and the early ’90s. Any group that became popular in the early ’90s as part of grunge or alternative rock is deeply indebted to both Greg Ginn and the artists he supported on his label. Truthfully, the band’s output is a mixed bag; some of their records are stellar (Nervous Breakdown, Damaged, First Four Years, Live ’84) and others are borderline dreadful (Slip It In, Loose Nut) but their live performances were consistently exceptional. In my estimation, Black Flag’s high points and their legacy far out-weigh the band’s low points. All things considered, Black Flag and SST Records laid the groundwork for most indie music that was to follow and wrote some damn fine songs in the process.

Note: If anyone has any interest in Black Flag or hardcore music as a whole, I heartily recommend the documentary American Hardcore. The footage is great and many of the interviews are insightful and amusing.

1. Of course, there were exceptions to this. Darby Crash, the front band of L.A. punk band The Germs, had a serious opiate habit and eventually took his own life by intentionally over-dosing on heroin. Black Flag’s first singer, Keith Morris, was also a big fan of controlled substances. For the most part though, hardcore participants were your run-of-the-mill high school burn-outs and disaffected surf brats. They drank prodigiously and liked to get into fights (clearly, these two activities bear no connection).

2. (!!!!!!) There’s a method to my madness, readers.

3. The ominous name came from a brand of popularly-used insecticide. Go figure.

4. Reyes can be seen as the singer of Black Flag in Penelope Spheeris’s documentary Decline of Western Civilization Part 1, which portrayed the Los Angeles hardcore scene as it existed in 1980.

5. This is the inverse of Metallica’s notorious Haircut-gate, no?

6. Punk was always a boys’ club but hardcore was almost entirely comprised of males. Few fans were female and of those women who attended hardcore shows, many of them were groupies (Black Flag had a reputation for being groupie hounds). Roessler would eventually marry Mike Watt of the Minutemen, whose band was also signed to SST.